Another thing about the novel Henry that I wrote when I was 19 (see previous post): it was written the present tense, and it took place in a stripped down world like a stage set, advertising its own artificiality. At that time I wanted to get away from the formal pretence of the conventional novel that it was narrating events that had actually happened in the real world*. My idea was that, insofar as the events in the book could be said to ‘happen’ at all, they happened in the reader’s head, at the moment that he or she visualised them. Hence the present tense.

I wasn’t at all well-read then, in terms of literary fiction, and even less so in terms of any kind of literary theory, but this was the seventies, and I seem to have been picking up something of the zeitgeist. “fuck all this lying,” the sixties experimental novelist BS Johnson wrote towards the end of a novel that was nominally about a would-be architect, “look what I’m really trying to write about is writing not all this stuff about architecture trying to say something about writing my writing”. On Saturday, in an interview in the Guardian which prompted this post, a more recent experimental novelist, Will Self, observed in a similar vein: “You can’t go on pretending that the writer is an invisible deity who moves around characters in the simple past. I just can’t do that stuff. It’s lies. The world isn’t like that any more.”

I suppose it’s the same sort of thought that led some abstract painters to turn away from the pretence that a painting was a representation of the three-dimensional world. A painting was, and could only ever be, an arrangement of colours and shapes on a flat surface. Why pretend otherwise? Why lie?

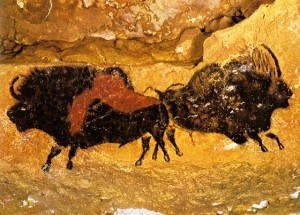

I don’t feel that way now (as will be apparent from the fact that my books are narrated, pretty conventionally, in past simple tense, as if the events have actually happened). It seems to me that painting has a pretty long history (over forty thousand years!) of representing real world objects. That, in a way, is the magic of it. (This picture is a bison, and at the same time it isn’t!) And story-telling must surely have an equally long history of narrating imagined events as if they had really happened.

I know we get bored of particular ways of telling stories, and need to try new ones, one of which is to draw attention to the artificiality of the story itself. But this too gets boring after a while.

* * *

*In most SF novels, by the way, things are more complicated: the content of the story pretends that the events described lie in the future, while the grammar pretends that they are in the past.