Dark Eden being selected as reading material for the Green Belt Festival (see previous post) has made me think about the legend of Eden.

I say legend. There are still those, of course, who claim to believe the story is literally true. This is a pretty preposterous claim to make in the modern world (at least by any half-way educated person), but, as I’ve observed before, it takes an almost equally preposterous kind of literal-mindedness to think that, because a thing isn’t literally true, it isn’t true in any sense at all. Clearly this legend has some resonance for me – is, in some way, true – or I wouldn’t want to use it as the starting point for a novel. So what does it mean to me?

I think there are two aspects of the story in particular that have always seemed powerful for me. One is the snake: the idea that even in the most idyllic scene there is always somewhere a flaw, a danger, a threat (like the ‘invisible worm’ in William Blake’s poem, ‘The Sick Rose’). The other is the idea of expulsion: the idea that, for some reason, human beings are cut off from their true home. This is the idea I drew on for Dark Eden, in which a little band of people are cut off not only from the rest of humanity but even from light, and have to live out their lives in the knowledge of that loss.

The same sense of loss, it seems to me, is present in Plato’s notion of humanity huddled in a cave and seeing, not the real world, but shadows on the wall. This rings true for me. It feels like the way things are.

Why it does, is another question. Psychoanalytic psychology would, I think, explain this subjective sense of loss in terms of a child’s painful discovery that parental comfort and love is not always available, that things are not and never can be perfect. That rings true for me as well. In the world of Dark Eden, the particular focus of people’s sense of loss, was their Eve figure, Angela, the mother of them all. Even John Redlantern, who was determined to break away from the past, was particularly devoted to Mother Angela (a police officer from Peckham on her way to goddess-hood), being himself in some ways motherless.

***

Anyway, these reflections prompted me to go back and look at the story as it appears in the Bible. (I was going to say the ‘original’, but in truth, this is surely a story that evolved over many thousands of years before it was ever written down, and it shares obvious characteristics with other creation myths in other traditions, suggesting a remote common ancestor. As I’ve observed before, stories have a life of their own. They travel, they have adventures, they change their clothes, they make new friends…)

What struck me immediately about the version in Genesis is its mythological, child-like, fairytale-like quality. God is pretty much human. (He walks in the garden in ‘the cool of the day’. He appears surprised by events). The snake is a talking animal. (No suggestion that it is anything more.) And, much as Norse mythology offers fanciful explanations for everyday things like the morning dew (it is the world weeping for the God Balder) or the tides (the result of a prodigious drinking feat by the God Thor), so the Eden story offers explanations for why snakes crawl on the ground, why women hate snakes, why childbirth is painful, and why farming is backbreaking work.

And, just as in fairytales and other mythologies, ludicrously obvious things are somehow overlooked for the sake of the story (I think of the Norse legend of Balder, in which the goddess Frigga secures a promise from everything in the earth and sky and in the sea not to harm her son, but doesn’t get round to securing it from mistletoe, which lives neither on the ground, or in the sky, or in water), so here God plants a fruit tree that he apparently doesn’t want people to touch, right in the middle of Eden.

But above all what struck me was God’s motive for expelling Adam and Eve from Eden. It really isn’t because they have committed a terrible sin (how can you commit a sin before you have acquired the knowledge of good and evil?) but because, by eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, ‘the man is become as one of us’ and must be expelled ‘lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever’. The expulsion is the act of a jealous God heading off a potential rival.

Above all, what strikes me about the story, on re-reading it, is that it isn’t just about loss. It is also about gain, about people moving from a baby-like or animal-like state to become adult human beings. Which is surely a good thing, and surely something that had to happen, and surely the reason why, if there was a God, he or she would plant a Tree of the Knowlege of Good and Evil in a place where, sooner or later, someone would surely decide to try the fruit, talking snake or not.

So the two elements that were most powerful to me – the loss, and the snake – seemed on re-reading to be far less central than I had remembered them. The great thing about these kinds of story, with their ambiguities and their layers, is that we can different things in them, each time we look. (The great thing, but also the dangerous thing. You can mine misogyny from this story if you want to, it seems, though I can’t myself see that Eve is held much more to blame than Adam. You can even apparently, though this really does require considerable ingenuity, derive the idea from it somehow that humankind is so wicked as to deserve eternal torment, after death as well as before it.)

***

Could there have been a real historical moment, which in some way corresponded to the Eden myth? I suppose it would have been millions of years ago, somewhere in Africa, when some proto-human ape, for the very first time, had some dim glimmer of a insight: ‘This world isn’t just about me, my desires, my instincts. Other creatures have feelings too.’ For such an insight, surely, is the real first step towards a knowledge of good and evil?

But of course that wouldn’t be a one-off event. It would happen again and again. It still happens now.

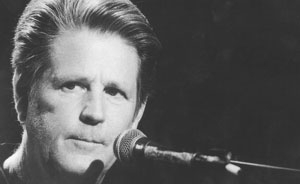

I referred to the work of Philip Dick previously as something that I particularly admire. Here is another tortured Californian who I also admire. I’ve seen him perform a couple of times in recent years, on his Pet Sounds and Smile tours of the UK. The beautiful clear voice of his youth has gone, and, of all rock stars, this frail-looking man is surely the most uneasy and vulnerable on the stage, to the point where the audience seemed to me to be not just applauding him, but reassuring him of its love so as to help him keep going. But his music as ever is sublime, soaring, stately, and, despite his abusive childhood and his precarious mental health, peaceful and full of hope and love.

I referred to the work of Philip Dick previously as something that I particularly admire. Here is another tortured Californian who I also admire. I’ve seen him perform a couple of times in recent years, on his Pet Sounds and Smile tours of the UK. The beautiful clear voice of his youth has gone, and, of all rock stars, this frail-looking man is surely the most uneasy and vulnerable on the stage, to the point where the audience seemed to me to be not just applauding him, but reassuring him of its love so as to help him keep going. But his music as ever is sublime, soaring, stately, and, despite his abusive childhood and his precarious mental health, peaceful and full of hope and love.