I spent the week before last in a place on the coast of Morocco called Oued Laou with two old friends, Clive and Jonathan. Jonathan has a small house there and speaks Moroccan Arabic, which earns him huge respect.

The last time I visited him there, the trip inspired my story The Peacock Cloak. On the hills around the town, cistus flowers, admired by Tawus at the beginning of the story, grow in great profusion.

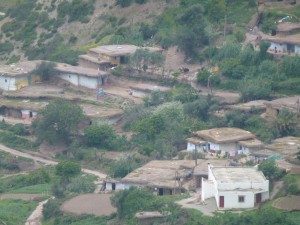

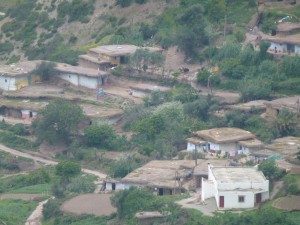

Much of the ground, though, is intensively cultivated by small subsistence farmers who grow wheat, barley, peas, lentils, onions and figs, all packed in tightly together, and keep goats, sheep, cows and chickens.

They live in very small and simple single-storey houses consisting of a brick wall, topped with flat layers layer of branches and twigs, and then a covering of loose earth (though some of them now have added a polythene membrane, a solar panel, or even a power line). As I looked out at the little hillside village below I imagined people living pretty much as they do now in houses pretty much like these for thousands of years, while successive invaders – Romans, Vandals, Arabs, Spaniards – broke over them like waves with their various projects of subjugation/improvement/religious conversion/enlightenment/ modernisation. Just like Tawus.

And like Tawus too, we found ourselves to be the objects of fascination and even wonder. One old woman stood with her hand over her mouth as if to stifle shrieks of incredulity, while her more confident daughter questioned us sharply about ourselves. Where did we come from, France or Spain? (There were only two options, I understand.)

They insisted we came in for mint tea and fried eggs. The goat wandered in after us and settled down comfortably in a corner of the bare earth floor. The daughter looked across at it and drew a finger over her throat to indicate the goat’s fate after Ramadan, telling us of the many uses to which its meat and skin would be put.

The tea was like polo mints dissolved in water. The eggs were delicious too.