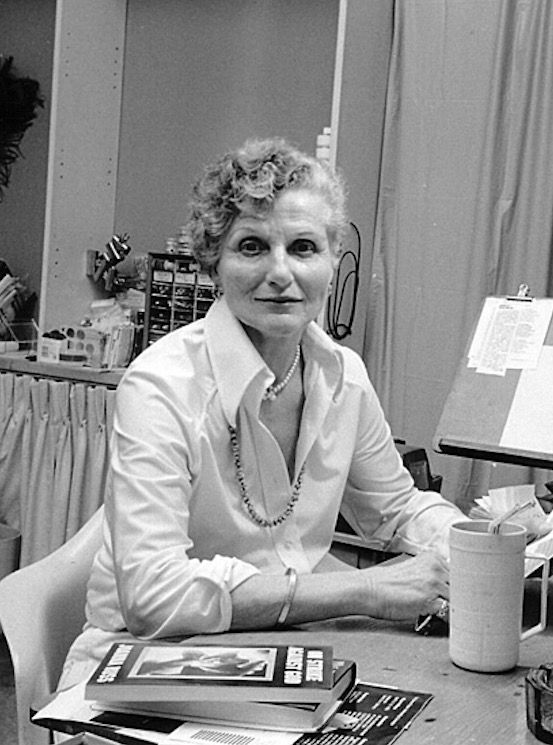

Alice Sheldon, 1983, aged 58, four years before her suicide: Photo by Patti Perret

Alice Sheldon (‘Alli’) wrote science fiction mainly under the name of James Tiptree, Jr. Some while back, I wrote an appreciation of her stories here. Of all science fiction writers, she and Philip Dick are the two I feel the closest affinity with.

Alli liked to correspond on a friendly basis with editors and with other writers whose work she enjoyed. Her penfriends included Joanna Russ, Frederick Pohl, Ursula le Guin, Robert Silverberg, Gardner Dozois and Harlan Ellison. I’d like to think that, if I’d been older and my writing career had started ten or twenty years earlier, I might have been one of her penpals too. I think she might have liked my stories -some of my stuff, including the novel I’m struggling with right now, is thematically quite close to hers- and she made a point of contacting writers whose stuff she liked. But in fact she died – she shot herself, to be precise, after first shooting her blind husband in his sleep – three years before my first story appeared in print. (My first ever published story, A Matter of Survival, was about a nation of men at war with a nation of women, a very Alice Sheldon subject.)

The odd thing is, though, that if there had been an overlap between our careers and I had been her penpal, I, like all the people I’ve just listed, would have believed I was writing to a man. Because James Tiptree wasn’t just a pen-name for her stories, but the persona under which, over some years, she engaged in all this correspondence. It wasn’t just superficial stuff, it was often quite deep and intimate, yet it was all signed off by James Tiptree.

I’ve been reading her biography by Julie Phillips. Alli (I’m calling her that because Julie Phillips does, and because Sheldon was her married name and not a name she had from birth) was the only child of a wealthy Chicago family. Her parents were adventurous people with the resources to have big adventures. As a child Alli was taken on trips to Africa – living in the bush, hunting, visiting remote communities… – and her mother was a successful writer who also did lecture tours in which she regaled audiences with tales of these adventures. Alli herself grew up as a vigorous, outdoorsy sort of person who liked riding and fishing and shooting.

She was a painter for a while. In the war she was a photo analyst for the army, and went on to do this work for the CIA, which is where she met her second husband, Ting, who was 12 years older than her and came from a similarly elite background. Ting was who she lived with for the rest of her life and eventually killed, believing this to be an act of kindness.

She wanted a child but wasn’t able to have one. She studied psychology and engaged in psychological research. She enjoyed ‘masculine’ pursuits and the company of men, though she was sexually drawn to women. She suffered from depression. She had a difficult relationship with her mother, loving in a way, but intense and stifling. And when I say stifling, I mean stifling. Alli told Joanna Russ that, when she was fourteen, in a stateroom on a ship, her mother had ‘more or less openly invited me to bed with her’.

My main criticism of Phillips’ excellent book would be that she doesn’t dig deeper into this episode. I can appreciate the difficulty of doing so in the absence of any other material, but to be sexually propositioned by a loved parent -and in fact even just to have the sort of enmeshed, boundaryless relationship with a parent in which that is even thinkable – is liable to turn the rest of your life into a knot that can never completely be undone. Nothing quite makes sense any more. The things you most long for are also the things you dread. You’re like a circuit board with the components linked up wrong so that the switches don’t do what they’re supposed to do: lights that are supposed to come on at the same time don’t do so and others that aren’t supposed to come on at the same time, nevertheless always do. The fact that 14-year-old Alli was tempted to say yes to her mother’s proposition, and never blamed her for it, doesn’t alter that fact – it just shows how tangled things already were. I wonder what else happened that Alli never chose to share?

Anyway, when you know about that, you can certainly understand better why she wrote stories like ‘Love is the Plan the Plan is Death’ in which the spider-like narrator is slowly being eaten alive by his mate.

Tiptree was unmasked as Alice Sheldon in 1976. (He had told his correspondents about his mother’s death, and people looked up the obituary notices in the Chicago papers and worked it out.) Alli was frightened that all her pen friends would be upset by the deception and desert her, but it seems that everyone, men and women, reassured her of their continued friendship. Ursula le Guin wrote her a particularly lovely letter, welcoming her as a ‘sister soul’.

I found the chapter in which Tiptree unravelled particularly powerful. It reduced me to tears in fact. It was touching to see le Guin and others welcoming Alli as a woman friend but it was also obvious that something important to her had begun to fall apart, something that had made it possible for her to share her inner self, and yet feel safely hidden. I think of a spider creature again, one that longs to join with others, but fears being devoured.