Some further, possibly not very coherent, thoughts carrying on from a previous post. In that post, I expressed my increasing dissatisfaction with TV nature documentaries which, on the one hand, mainly show scenes of predators hunting, or male animals fighting for control of females, accompanied by the kind of tense, exciting, sinister music that I associate with action scenes in movies, and on the other invite us to see nature as something fragile and vulnerable and in need of protection. Why is an orca drowned in a fishing net tragic and pitiful, but a baby seal being tormented by orcas a thrilling spectacle?

Continue reading “Of the Devil’s party without knowing it”Category: BEST POSTS

Nature

I watched the BBC series Wild Isles, presented by David Attenborough. It was beautiful to look at, but it left me wondering about ‘nature’, as presented by these programmes.

In the first episode we were shown a pod of Orcas off the coast of Shetland (or was it Orkney?). I’ve watched enough of these shows to know the kind of spectacle we can expect from Orcas – they typically harry their prey to a slow and terrifying death and I still vividly remember, from Attenborough’s Arctic show, the closeup shot of an exhausted seal looking straight at the camera, as orcas dragged it off an iceberg to be torn to pieces. It felt wrong to be staring into its eyes.

This time round a baby seal, which had swum out some way off the shore, was caught by a member of the pod. The orca then took it, still alive, to a group of its companions, where, after a certain amount of playing with its victim, the successful hunter demonstrated to younger orcas -Sir David sounded quite aroused at this point- how to hold it under water and drown it.

Later on, though, we were shown an orca that had itself drowned in a fishing net. Sombre music played. This drowned cetacean was apparently a tragedy, while the slow torment of the baby seal had been presented as something rather thrilling. Why, I wondered? Why should I care about one and not the other?

The same pattern persisted throughout the series. Predators hunting and killing -and quite often targeting the young of their prey- dominated most episodes, and were presented as an exciting spectacle, accompanied by rousing, if sinister, music,as you might hear in an action scene in a movie. We were being offered animal-killing as a voyeuristic entertainment, not unlike the animal slaughters that the Romans put on in their arenas, except that this was ‘nature’ so we could savour it guilt-free. But then there would be a sudden switch of tone and talk about the fragility of ‘nature’ and the need to protect it from the depredations of humanity. I found this no longer worked for me. I grew bored of the slaughter, and even sickened by it, and it certainly didn’t put me the mood for ‘only man is vile’ pieties. My thoughts were more on the lines of Kurtz in the Congo jungle: ‘The horror, the horror.’

After hunting scenes, the next most frequent dramas depicted in these shows are the endless combats between male animals fighting to obtain, or defend, access to females. In one episode a huge, repulsive male seal spotted an equally huge and repulsive rival that had emerged from the sea, and flopped and wriggled his blubbery bulk across the sand to do battle. They ripped each others flesh, they roared, they reared up to look as big as possible. The much less repulsive female seals meanwhile hurried to get their babies out of the way, because the males in such battles are apparently so indifferent to anything except their need for dominance, that they will crush their own children to death without a thought if these are foolish enough to get in their way.

It all felt rather familiar actually, like the story-line for much of human history. Not so much a case of ‘only man is vile’, as ‘nature is vile, and we’re a part of it.’

See also:

Kite Strings

I’m not a fan of big C Conservatism, but I have a definite streak of small c, in that that I am suspicious of the impulse to trash traditions, rules and taboos, just because they are traditions, rules and taboos. To re-use a metaphor from one of my stories, a kite string may seem to be holding back the kite that strains against it, but in fact provides the rigidity that enables the kite to fly. Cut the string and the kite comes flopping down.

It’s not a universally applicable metaphor, obviously, but it’s worth thinking about before cutting a string (the monarchy, for instance?). I think I see society as a huge kite with multiple strings: you can cut them, but don’t cut too many at once, and don’t cut them without putting new ones in their place.

One of the objections I have to big C Conservatism as it exists now is that, at bottom, it is not actually conservative in the small c sense. It postures as small c conservative by ritually defending certain old fashioned symbols, but this is largely cosmetic. Modern political Conservatism, in fact, is a reckless cutter of kite strings. Greens and socialists are, in many respects, more conservative than Conservatives.

Cancer? Who cares?

[Soundtrack for this post: 5.15 by The Who.]

A short while ago, in a more than usually neurotic moment, I briefly persuaded myself that I might have lung cancer. (As far as I know I don’t.) This made me think of a time, over half a century ago, when I was 16. Our school had organised a lecture about the harm caused by smoking. The doctor who gave the talk had some bucket-like boxes on stage with him and at a certain point, he opened these up and, to our slight incredulity, took out a number of cancered lungs, flattened and encased in clear plastic, which he passed round for us to feel. The healthy parts of the lung felt soft and spongy, he pointed out, but the cancered parts were hard unyielding lumps.

We felt the lumps, and they were nasty, but we were unmoved. After the lecture was over, my friends and I headed off to one of our usual smoking spots to roll up moist, aromatic Old Holborn tobacco into unfiltered cigarettes, and draw in the rich, tarry smoke. I smoked so greedily back then that I often finished when my friends still had half a cigarette left, and tried to scrounge drags from theirs. If I smoked a manufactured cigarette, I would draw on it so hard (my poor lungs!) that the filter sometimes fell apart in my mouth.

Remembering this from the perspective of someone who thought he might have lung cancer, I felt briefly angry with my past self for his utter indifference to my well-being, but the feeling didn’t last. The thing is that, while I can remember being that 16-year-old, and still have that 16-year-old inside me – for better or worse, it was the most intense and vivid time of my life – the reverse is not the case. I was not inside him. He had no sense at all of his future self in fifty years time. Me, as I am now, was a complete stranger to him, far more so than, say, my grandfather, then just 7 years older than I am now.

In fact, never mind fifty years time, I had no sense of myself in five years time, no idea where I was going, let alone how I was going to get there, other than a vague sense of wanting to be a writer, or a rock star, or something of that kind, which I suppose represented the possibility of being able to continue to play, to hold onto some aspect of being a child.

All I really understood was the tiny universe of my school where I lived as a boarder, cut off from the rest of the world. The one imperative I felt was a need to draw a line between myself and the adult world, and the values and forms of authority that the adult world accepted. Even to think about my future in a constructive way would have been to do what the adult world wanted me to do, so that to attend to what the doctor said, and do something about my smoking, would have been a kind of surrender. To free myself from the past, I had also to deny my future.

That’s how it felt at the time, and even now I can enjoy in retrospect the feeling of defiance involved in rejecting prudence, forethought and common sense as so much boring, grey, bourgeois claptrap. Of course, I now also see the fear and desperation that lay behind this -and the timidity that actually controlled me – but it wasn’t just fear, it was a need to break free from a stale mold that others wanted me to fill, even if this meant casting myself naked into the world, and even if it meant doing myself harm.

Heredity versus Merit

Speaking very broadly, the political choice in many western countries boils down to whether heredity or merit should be the basis of structuring society. (Or so I suggest.)

Those on the ‘heredity’ side argue that people should be allowed to accumulate wealth, keep it, and pass it on – along with he benefits that come with it – to their children or whoever else they wish. This idea obviously appeals to those who are already rich, which is why the rich tend to support parties that espouse it. But it also appeals to those who aspire to be rich, or for whom financial success is the primary metric by which they measure their success in life. It also appeals to people who just dislike the idea of the state interfering in their affairs.

All political factions promote and defend certain interests, or classes, but they also promote moral principles that seem to endorse the stand they take. They fly flags, as it were, that give moral cover to the preferences of the interests and classes they support. Parties that support the hereditary principle – we call them right-wing or conservative- tend to fly one or more of the following flags: FREEDOM, FAMILY, TRADITION, PROPERTY RIGHTS, LOYALTY TO ONE’S OWN, OPPOSITION TO OVERBEARING GOVERNMENT. Their opponents see these flags as nothing more than a cynical cover for self-interest.

Those on the ‘merit’ side, on the other hand, argue that heredity is a bad way of determining who rises to the top, it holds back people from poor backgrounds, and gives a free ride to people from rich ones. We should all be allowed to rise on the basis of our own talents and hard work. This idea appeals, of course, to those who have themselves risen to – or maintained- their present position through their own talents and hard work, and to those who feel their own talents and hard work have been held back, or have not sufficiently been rewarded. And it appeals to people for whom the metric by which they measure their success in life is not simply money, but things like educational attainment, professional esteem and recognised achievement. So the ‘merit’ idea tends to appeal to people such as academics, artists, journalists and other professionals, who earn a living based on their own knowledge and skill, and in a context where non-financial metrics of success are available. (I’d suggest, for instance, that more such metrics are available for, say, a university lecturer, than for the owner of a haulage business: the former can become eminent among her peers for her knowledge, her publications, the originality of her thinking. The latter is, of necessity, more focused on making money as a way of showing that she is doing well.)

Parties that support the merit principle tend to fly one or more of the following flags JUSTICE, EQUALITY, FAIRNESS, RATIONALITY, SCIENCE, EXPERTISE, OBLIGATIONS TO THE WORLD IN GENERAL, A BENIGN AND INTERVENTIONIST STATE. Their opponents (of course) dismiss these flags as a cynical cover for self-interest. (For instance, while the partisans of ‘merit’ esteem scientific expertise, its opponents sometimes suggest that so-called experts are merely bigging themselves up into to enhance their own standing and make money. There is sometimes something in this.) These days, we tend to refer to those on the ‘merit’ side as liberals or ‘the left’, though both these terms have meant different things in the past, and they have certainly not always meant the same thing as one another.

Few people, even the most conservative, would completely dismiss the argument for ‘merit’ (though you only have to read a few novels from a couple of centuries ago to see that, in the past, earning a living through ones own professional skills was seen as much lower status than living on the rents from accumulated capital). Similarly, in practice if not in theory, few people, even on the ‘merit’ side, completely dismiss the hereditary principle. Even people who vote consistently for parties that are on the ‘left’ or ‘liberal’ side, tend to accumulate at least some wealth if they can, and pass at least some of it on to their children.

But one point that isn’t so often made is that both heredity and merit entail a good deal of luck. It’s lucky to be born rich, yes, but it’s lucky also to be born with above average ability or a special and marketable talent. Some people are born with neither – a lot of people actually – but they have to choose between the parties of ‘heredity’ and those of ‘merit’, asking themselves under which kind of regime – which set of flags – will it be more comfortable to live? Their choices have been less predictable of late. And perhaps this is wise. It’s never a good idea to let people assume your support can be taken for granted.

See also:

Two kinds of game

Having a 3 year old granddaughter has got me thinking about children’s games. There are two kinds, I think. I’ll call them role play games and literal games. Role play games are the ‘let’s pretend’ kind: cops and robbers, mummies and daddies etc. Literal games are the kind where no pretence is required but the players agree to follow a set of rules and to pursue some goal that the game itself defines: tag, for example, or any sport.

My dear granddaughter is too small to make this distinction. All games are role play to her. If she and I play hide and seek, she will hide in the same place every time it’s her turn to hide, and still expect me to search the house for her, muttering ‘where can she be?’ When it’s her turn to seek she will still go from room to room telling herself ‘no, he’s not in there’, even if I’ve stayed put and simply pulled a rug over my head. She enjoys the game very much (as I do!), and is always charmingly delighted to find or be found, but it’s all role play. A rule-based literal game is either beyond her or, perhaps more likely, is simply of no interest.

Thinking about it, I realise that most games are a hybrid that includes both role play and literal elements. Monopoly for example is a literal game, in the sense that it has formal rules and a set goal, but a lot of the flavour of the game comes from the fantasy element provided by pretend money, rent and so on. Would it have caught on if the properties were just called ‘colour squares’, the money was just called points and instead of ‘go to jail’ the card just read, ‘move counter to square ten’?

How about a game like football, though? In a way that is a purely literal game, in that the players are not pretending to do anything they are not doing in fact. But football fans don’t follow it as a literal game. To be sure, part of their enjoyment comes from admiring the skill of the players, but much of the excitement comes, doesn’t it, from that powerful identification with one side or another, which allows supporters to refer to ‘their’ team as ‘we’ – and from the whole mythology that is constructed around the teams: their histories, their reputations, their ancient rivalries… Formally speaking, football may be a literal game but its phenomenal popularity comes from a role play game that’s built around it, in which fans ‘pretend’ they are directly involved in the contest and are not simply observers and paying customers.

I was born without this particular gene myself, but otherwise sensible grownups have assured me that they can feel emotionally devastated when ‘their’ team loses. It’s safe emotional devastation, though, isn’t it? Not like the kind that comes from being dumped by your partner, or your house burning down. Role play is meant to feel as real as possible without actually being real: real enough to provide some catharsis, not real enough to upturn your life.

And now I’m on this track it strikes me that, even for the players of apparently literal games, there is a psychological role play going on, for otherwise why would it matter if you won or lost? People who enjoy playing literal games are not dispassionately following rules. They are engaged in a psychodrama about overcoming danger and obtaining mastery.

For some people, this isn’t ‘real’ enough, and they need to do things that really are objectively dangerous like free solo climbing, or becoming a mercenary. And here we move beyond games into the ‘real’ world, which itself consists of activities that resemble literal games – you follow certain rules in pursuit of goals such as money or success – but often get their flavour from the possibilities they provide for psychodrama, and very often require the playing of roles.

So on reflection the distinction between literal and role play games seems less clear than it did when it did when I started. At some point my granddaughter will no longer be satisfied with pretending to hide and pretending to seek and will want to really hide and really seek – but the pleasure she takes in the game and her motivation for playing it may not be so very different.

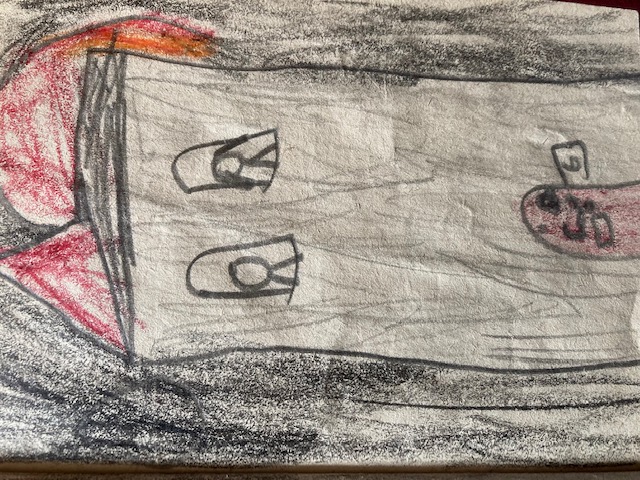

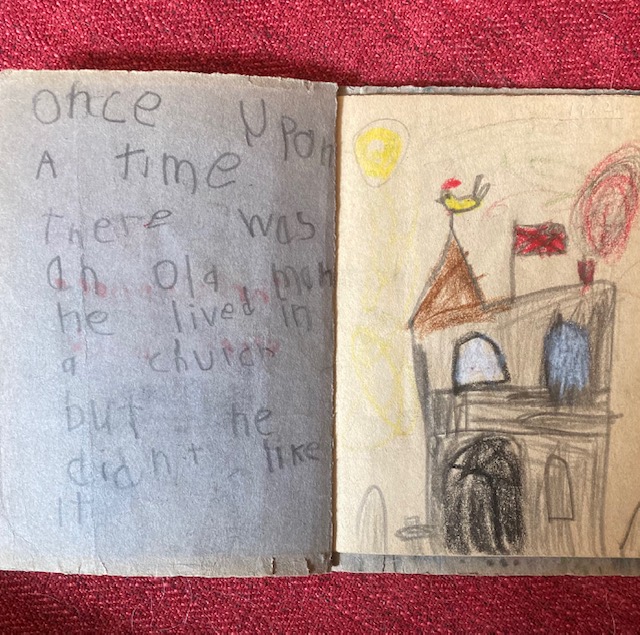

A very early work

I have a story which I wrote when I was four or five.

The full text is as follows:

Once upon a time there was an old man he lived in a church but he didnt like it

The man cried very loud so he said I want a house to live in

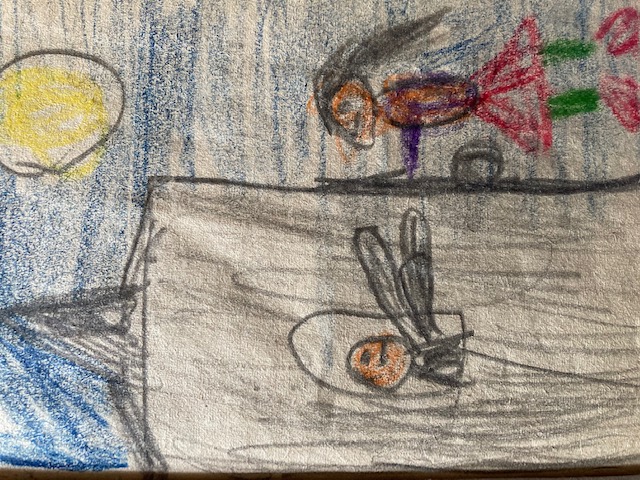

He heard the door bell He peeped out of the window and saw somebody he would like

Now it was evening and the person said can I live with [you]

Yes please said the man

I will said the person.

They lived in a lovely cottage and they loved it and they wouldnt move house again

A smart car came to fetch the person but the person said I dont want to go

and the man in the smart car said you must go

and the old man shot the man in the smart car

Funny thing is, the story works pretty much like the stories I still write. It takes things from my own life and and mixes them up with imaginary things. There are recognisable autobiographical elements: I had not long moved from a terraced house to a large hollow house which might well have seemed like a gloomy church.

Sometime before that, when I was less than 2, so it may well already have been outside of my conscious memory, an au pair girl who had looked after me – and (so I now hypothesise) was warm and fun compared to my depressed and unpredictable mother – had returned to Germany, presumably collected in a car (by a boyfriend, perhaps, or maybe just a taxi driver?)

I’ve been told I was very distressed by this, so it seems to me that this story might have been a rewrite of that painful scene but with the difference that its protagonist had some power – murderous power, no less! I like the old man’s smile as the smoke and flame comes out of his gun.

There’s a primitive magic in stories and pictures. It’s as if at some level we think by naming or depicting things, we can control them.

It’s interesting to me how the old man is allowed an age and a gender, but ‘the person’ is given neither, even though in the pictures she is clearly a woman or girl, as if this was someone I wasn’t supposed to name. (Or maybe I was just coy about admitting I liked girls.) I like how the old man reaches out towards her from his window with both arms when she’s still outside his front door.

Idea for an Alternate History

The so-called culture wars have a tendency to map all debates into two pre-existing camps: us and them, and this can result in certain positions becoming associated with one side or the other in a way that seems almost arbitrary. (Why, for instance, would we associate concern about the environment more with social liberalism than with social conservatism?)

This polarising tendency appears to be particularly pronounced in America but my sense is that it is more pronounced in Britain than in other European countries. If this is true, I wonder whether it is a product in part of ‘first past the post’ electoral systems which tend to result in a competition for power between two dominant parties, and make it hard for third parties to make headway? (For isn’t that what we mean by ‘culture wars’: the intellectual equivalent of an adversarial two-party system?)

Anyway, I think it may be partly as a result of this kind of binary thinking, that Liberalish, Remainish people often lump the Brexit vote together with the election of Trump, as if they were exactly the same phenomenon. This is understandable but lazy. Of course there are large overlaps, but there were people who voted for Brexit who wouldn’t have dreamed of voting for Trump, and there were reasons for voting Brexit that had nothing to do with Trump-style nationalism.

So much of politics is about projection. ‘We’ project things we don’t like onto ‘them’ and mock the things they value, while projecting everything that is good and virtuous onto the things we do value. Indeed the very fact that ‘they’ despise something, makes us value it even more, to the point of uncritical idealisation.

A narrative emerged among some Remainers, for instance, in which they mocked or condemned patriotism but declared themselves proud Europeans. But is there any moral difference between identifying with a country and identifying with a continent? (If there is, I’d be interested to know what exactly is the the land area required for identification with a piece of territory to become virtuous?)

Breaking away from larger entities, defending the integrity of large entities, and joining together to form larger entities are, it seems to me, all quite common political processes. They can all be presented as progress, and can all in different circumstances be associated with political positions that may be described as left-wing, right-wing or neither.

I find myself imagining a parallel timeline where it’s the right-wingers who are the biggest fans of the European project, because they want to enhance and perpetuate the global power of the wealthy, developed, culturally Christian countries that once divided the world between them. and it’s the fascists in particular who want to unite the ancestral homeland of the white race into a single giant state. (The lefties in this universe would be advocates for organisations such as the Commonwealth or the Francophonie that build links between countries across the global North-South divide.)

If you imagine something that seems plausible, it sometimes turns out to already exist. (I didn’t know that ‘rogue planets‘ were really a thing, for instance, until after I’d invented one for a story.) After writing the above, I learned that the British Fascist leader, Oswald Mosley, did indeed advocate uniting Europe into a single state.

Worldbuilding

Someone quoted the following quite widely-cited passage from M John Harrison in something I read recently:

‘Worldbuilding is dull. Worldbuilding literalises the urge to invent. Worldbuilding gives an unnecessary permission for acts of writing (indeed, for acts of reading). Worldbuilding numbs the reader’s ability to fulfil their part of the bargain, because it believes that it has to do everything around here if anything is going to get done.

‘Above all, worldbuilding is not technically necessary. It is the great clomping foot of nerdism. It is the attempt to exhaustively survey a place that isn’t there. A good writer would never try to do that, even with a place that is there. It isn’t possible, & if it was the results wouldn’t be readable: they would constitute not a book but the biggest library ever built, a hallowed place of dedication & lifelong study. This gives us a clue to the psychological type of the worldbuilder & the worldbuilder’s victim, and makes us very afraid.’ [More context here]

Do I agree? Well, it depends what kind of worldbuilding he means. Some worldbuilding is necessary to any sort of story-telling – all stories need a context of some kind, and sometimes the context is at least as important as any of the characters – but some worldbuilding isn’t necessary in that way, and too much of it can be counterproductive, even if it doesn’t make us ‘very afraid’.

Of course Harrison is right that for a writer to construct a whole world is in any case impossible. Even to precisely describe a wooden chair would take more words than the word count of an entire library of novels. The reader must be allowed to do much of the work (work to which we are well accustomed, since in life also, we must assemble a sense of a complete world from a collection of fragments and guesses.)

Harrison’s own novel The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again is actually, I’d say, a rather good piece of worldbuilding. The story ostensibly takes place in contemporary England, partly in London and partly in the Midlands, but the setting is an imaginary place nevertheless, and one of the main pleasures of reading the book, and the thing that most lingered in my mind afterwards, is this place’s peculiar, queasy, dreamlike flavour. (The one moment that jarred for me was when the narrator mentioned ‘the debacle of Brexit’, thus ceasing to be the unfolder of a fictional world and becoming just M. John Harrison talking about this one.)

The Sunken Land is saturated with watery imagery: flooded fields, flooded houses, flooded gardens, dampness, houseboats, phials of muddy water, things that live in water, the River Thames, the River Severn, taps, kettles, toilets, a map of the oceans, the pools that form in sodden fields where you can still see grass and flowers beneath the glassy surface… This squelchy stuff, which all of us can easily assemble in some form or other from our own watery memories, comes together in the book to form an extended metaphor for the main protagonist’s depressed, sunken state (and, in a less clearly defined way, a metaphor also for the country we live in), so it’s absolutely essential to the whole enterprise that we enter into it. But he coaxes us to do this, not by precisely describing and explaining everything, which would be impossible (as he says), but by convincing us that he has immersed himself in it.

Lots of novels fail to do this. I have given up reading many books because I can’t experience their settings as anything more than clumsy cardboard cutouts, which no one has ever really inhabited. And if even the author hasn’t been there, why should I as a reader even try? But my point here is that this is worldbuilding, and there wouldn’t be much left of The Sunken Land without it.

What Harrison dislikes, then, is not worldbuilding per se, but a particular kind of worldbuilding in which the author gets over involved in making stuff up for the sake of it, fussily providing piles of detail which have no thematic purpose and get in the way of our own imaginations. The classic case of this is Tolkein’s imagined languages, alphabets and the whole vast historical/mythological backstory he created for the Lord of the Rings (though, to be fair, he summarised much of this material in appendices to avoid overloading the books themselves). Tolkein clearly had fun coming up with all this detail and, since I used to make up languages, alphabets and mythologies myself as a kid, I understand the pleasure of it. It’s the sort of activity that feels comfortable and safe because it’s intellectually engaging but also emotionally neutral, a bit like doing crosswords, or sorting out a stamp collection, or playing solitaire on your phone. (These days I look things up on Wikipedia that have no bearing on anything important to me at all. I find it restful.)

I don’t myself see anything sinister in this sort of activity, but it certainly doesn’t have much to do with story-telling, or the literary arts, and most of us probably wouldn’t want to feel that we’d spent too much time on it at the cost of other more lively and more outward-looking pursuits. It can be an escape from stress, though, and readers as well as writers find it so, which is where the ‘nerdism’ comes in. Some people enjoy absorbing themselves in the minutiae of imaginary worlds such as Tolkein’s, or J K Rowling’s. Some people learn to speak Klingon, or enact scenes from their favourite fictional universes, taking a holiday from the real world in those non-existent places. The kind of worldbuilding that Harrison disapproves of is (I think) the construction of these sorts of intricate non-places to hide in, something that is often referred to as escapism by those who dislike science fiction and fantasy.

I’m sort of with him. Yet at the same time I think it can be a hard line to draw, this line between necessary worldbuilding, which Harrison’s novel is a good example of, and the escapist kind which he despises and which, as he puts it, is not ‘technically necessary‘. After all, any novel or story, however literary, however serious, however engaged with painful and important topics, is necessarily in part an escape from the quotidian world, for writer and reader alike. Even a discussion such as this is in part a nerdy escape of that kind. Even the learned arguments that take place amongst eminent critics and distinguished scholars.

Utopia can wait

Two kinds of statement seem to come from the more radical wing of climate change activists:

(1) Unless we end greenhouse gas emissions in the next few years it will be too late and we will see a catastrophic collapse of civilisation and of the biosphere,

(2) We will only end greenhouse gas emissions if we completely get rid of the present capitalist political/economic system.

While I accept the possibility that both these statements may be true, I really hope they’re not, because there is absolutely no way that a completely new and fully functional political and economic system is going to be constructed in the next few years.

I mean, it’s not even as if we have blueprint of how such a system might work. You can’t just say you want ‘a society that values people more than profits’, or ‘a society that lives in harmony with nature’, and call that a plan! How are resources going to be distributed? Who is going to be in charge? (Oh, the people are going to be in charge are they? Is that the same ‘people’ who voted for the governments you say aren’t doing enough?) What is going to prevent the pursuit of short term gains that lead to long term harm? What incentives for work are there going to be? What is going to prevent the system being hijacked by its own elites, like Communism was? etc etc.

Lots of different kinds of people have their place of course, and this may in part be a matter of temperament, but speaking for myself, I am much less impressed, when it comes to combating climate change, by radical heroics than I am by meticulous practical work. XR cofounder, Roger Hallam, apparently thinks that nothing will change without a major insurrection that leads to large number of activists going to prison. I can’t see myself that large numbers of people being sent to prison will necessarily have the desired effect. I can imagine all sorts of possible consequences of insurrections of that kind, including the rise of authoritarian governments with no interest in climate change at all.

Remember that Lenin believed he was leading the Russian working class on the fastest route to socialism – and that Russia ended up with petro-capitalism and Putin.

Personally I’d rather see large numbers of people working on problems such as mass energy storage, affordable green fuels, and carbon neutral cement. It’s solving problems like these -and the political and business headaches that come with them – that’s going to stop climate catastrophe. Utopia can wait.