I’m chuffed that my story ‘Art App’ is included, with distinguished company, in this annual collection, beautifully edited by Donna Scott. The book is now available for pre-order from NewCon Press.

Blog, books, stories.

I’m chuffed that my story ‘Art App’ is included, with distinguished company, in this annual collection, beautifully edited by Donna Scott. The book is now available for pre-order from NewCon Press.

I’m proud and pleased to have had a story selected for this collection, which has been put together by Ian Whates at Newcon Press in honour of the late Eric Brown who died last year.

Eric was well-known and well-loved in the British science fiction world. He was a warm, gentle, unassuming man without a trace of arrogance or pretentiousness, and was an exceptionally prolific writer, not just in science fiction, but in many genres including children’s books and crime novels. Yet he’d never read a book until he was in his teens, when he first encountered the work of Agatha Christie. This (as Eric described it) opened up what felt like a magical and entirely new world to him to which he proceeded to dedicate himself, as a reader, writer and reviewer.

The stories in this collection are written by some of his many writer friends. Some of them (I’ve only read a couple so far) refer directly to Eric and his world. Mine doesn’t, but I like to think it’s a story he would have approved of, and perhaps even one that he might have written. It’s called ‘The Peaceable Kingdom.’

Here is the Guardian’s obituary for Eric (who was the paper’s SF critic for many years). The book is available now.

Here I am (on the right) signing copies of the Ballard-themed anthology, Reports from the Deep End at Forbidden Planet in London on Saturday. To my right are Maxim Jakubowski (who co-edited the book with Rick McGrath, as well as contributed to it), Pat Cadigan and Andrew Hook. Why do we SF people have such a preference for wearing black?

Chemo has made me even balder than usual. I’ve even lost all my nostril hairs. (This makes my nose drip suddenly and without warning, which can be embarrassing). But I’ve had my last dose of those horrible toxins and am on the way up. I came down to London on the train which I wouldn’t have attempted even a week earlier. It felt great to be doing things again.

I’m delighted to have a story in this Ballard-themed anthology, which will be out in the autumn (Nov 7th) – and in some very fine company too. I’m a big admirer of Ballard, particularly his short stories.

My contribution to this collection is called ‘Art App’. Ballard was an exceptionally painterly writer. His stories are not primarily driven by plot or character development, but by the accumulation and arrangement of very powerful images. I tried to honour Ballard’s attachment to Surrealist art and, in particular, to the work of Max Ernst, whose peculiar vision I only really became aware of as a result of reading Ballard.

Tomorrow is out in paperback today.

Many thanks to all the people who wrote to me in response to my offer to give away 12 free copies to celebrate.

I’m applying a very complex algorithm (?!) to those requests to decide on the winners (it includes such important metrics as ‘did the requester come from the same town as my grandfather?’) and will be sending out copies tomorrow.

If you weren’t successful, my apologies – I only have a limited number of copies to give away – and thanks very much for your interest anyway.

Although told from 250 years in the future, the main part of this book deals with a Cambridge-educated North London architect (Harry), and his relationship with a hairdresser from a small town in Norfolk who left school at 16 (Michelle).

When I described this to my friend Ian, his immediate reaction was ‘well, that would never happen’. You’d need to read the book to judge whether he was necessarily right, but it’s interesting, I think, that such a relationship seems so unlikely. I’m sure he wouldn’t have reacted in that way, if for example, I’d said the book was about a relationship between Harry and another architect who had, say, an Indian Hindu background. Nothing particularly unlikely about that. Which suggests to me that the cultural gap between different ‘cultures’ is actually smaller than the cultural gap between different classes.

Over much of my lifetime there was a kind of alliance between Harry’s class (which is also my own) -the liberal professional class- and the working class, both of which tended to vote Labour (just as both tended to vote Democrat in the US). In recent years, and notably in the Brexit vote, that alliance has fallen apart. Isn’t that what we really mean by the rise of ‘populism’? And that was the background against which I wanted to foreground Michelle and Harry’s relationship.

Two Tribes is out in paperback this week, so here’s a short post to celebrate. (More info about the book here.)

This is a book with a simple moral, which (adapting Solzhenistyn) could be summed up as ‘The line between good and evil does not pass between those who like the European Union and those who don’t.’

Or: ‘It’s a mistake to assume you’re one of the good guys, just because you and your friends think you are. Pretty much everyone thinks their lot are the good guys.’

Or: ‘Just because someone doesn’t agree with you about politics, doesn’t make them a monster.’

Although mainly set in the aftermath of Brexit, it isn’t really about Brexit. It’s about social class, and specifically about the complicated relationship between the liberal middle classes and the working classes in Britain, and the way that relationship is changing.

I’m very proud of it.

Here’s another moral. ‘When there is more than one elite, each elite condemns the elitism of the others, but denies its own.’

I’m looking forward to being a guest at a book group in Alaska this weekend. I won’t be physically present obviously (I wish I could be, the people who have invited me live in a place that looks absolutely amazing – see below). I’ll be joining them by Zoom.

For me getting used to meeting people via video link has been one of the upsides of the pandemic. It’s a technology that’s been around for some time, but I would never have thought of using it before this year. Yet, I’m not just using it as a substitute for meeting people in the flesh, I’m taking part in social events that previously wouldn’t have happened at all.

If you have a book group that’s meeting by Zoom and are looking at one of my books, feel free to contact me via this site.

Here’s the cover of my next novel Tomorrow. It won’t be out until July 2021, though it is already available for pre-order if you are keen.

The cover was designed by Richard Evans who also designed all the current covers of my Corvus books.

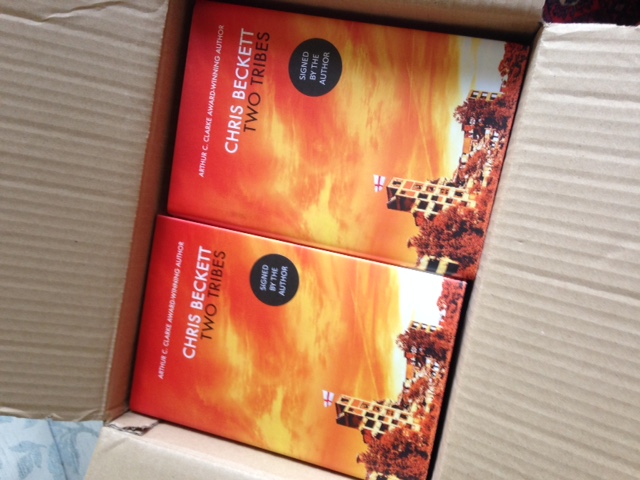

Six boxes of hardback copies of Two Tribes have arrived for me to sign for those who like collecting signed new editions. (If that’s your thing and you want one, you can preorder from Goldsboro).

The book will be out on July 2nd in hardback and as an ebook.

Most of it isn’t science fictional at all, but is set in London and Norfolk in the latter part of 2016 and early 2017. But the framing device is science fictional. The narrator is 250 years in the future, constructing the story from diaries and other sources, and giving herself a fair amount of license to guess things, or even make things up.

The story itself deals mainly with an architect called Harry who has recently separated from his wife and lives in London, and a hairdresser called Michelle who lives in a small Norfolk town called Breckham, and an unlikely and unexpected relationship between them.

The thing that prompted this book -or one of the things anyway- was a map of the results of the 2016 EU referendum, as they applied to East Anglia where I live. The whole region was a sea of ‘Leave’ but I happen to live in Cambridge, which was not only one of two islands of ‘remain’ in East Anglia (the other was Norwich), but the remainiest place in the entire country (75% remain). Yet an hour’s drive away, and in the same county of Cambridgeshire, Fenland was one of the leaviest (71% leave).

I voted remain, and have always had a warm feeling for the whole European project, so I was very saddened by the referendum result, but I thought to myself, how would it be if instead of looking at all this as me living in an island of correctness in a sea of error, or an island of decency in a sea of intolerance, I was to look at it more in the way that, say, an outsider looks at the political geography of Belfast.

Some areas of that city are strongly and publicly unionist, others are equally strongly and publicly nationalist, but from an outsider’s perspective this is not one group of people who are right and decent, and another who are wrong and bad, but rather two tribes, who have been brought up to have different allegiances, and have learned to see the same question in an entirely different way.

I think that’s how the great Brexit divide will look in a couple of hundred years for, after a certain point, when we look at the conflicts of the past, the issues being fought over lose their heat. And that’s the kind of perspective I tried to write from in this book.

In the case of the Brexit vote, there are factors apart from geography that inclined people to vote one way or another, and in particular I was struck by the fact that the ‘leave’ vote was proportionately higher in poorer areas of England (Scotland is different because Scots have the SNP) and in the poorer socioeconomic classes. (Cambridge is not only the remainiest but also one of the very richest parts of the UK.) So, as well as the two tribes of ‘remain’ and ‘leave’, I was thinking when I wrote this book of the two tribes that are middle-class people (and specifically the liberal professional middle classes of which I am undoubtedly a part) and working class people.

Being middle class is definitely one of my topics at the moment. I touched on it in America City, and also in Beneath the World, a Sea, and it continues to be a theme in the book I’m writing now. Most novelists are written by middle class people (or arguably all, since being a writer might itself be defined as a typically professional middle class occupation). As a rule that fact is simply a given, the base from which other topics are looked at, rather than as a thing to be examined in itself. But that’s what I’ve tried to do here.

Needless to say, I was also thinking about Frankie Goes to Hollywood.