Short stories

This is a complete list of my published short stories.

Blog, books, stories.

This is a complete list of my published short stories.

In the anthology To the Stars and Back: Stories in Honour of Eric Brown, (see post), edited by Ian Whates, from Newcon Press, published May 2024.

In the Ballard-themed anthology, Reports from the Deep End, edited by Maxim Jakubowski and Rick McGrath, from Titan Press. Published 7th November, 2023.

Reprinted in Best of British Science Fiction 2023, edited by Donna Scott, from NewCon Press, 2024.

Jointly written by Tony Ballantyne and myself, and based on an original idea of Tony’s. Published in Shoreline of Infinity 19, Nov 2020.

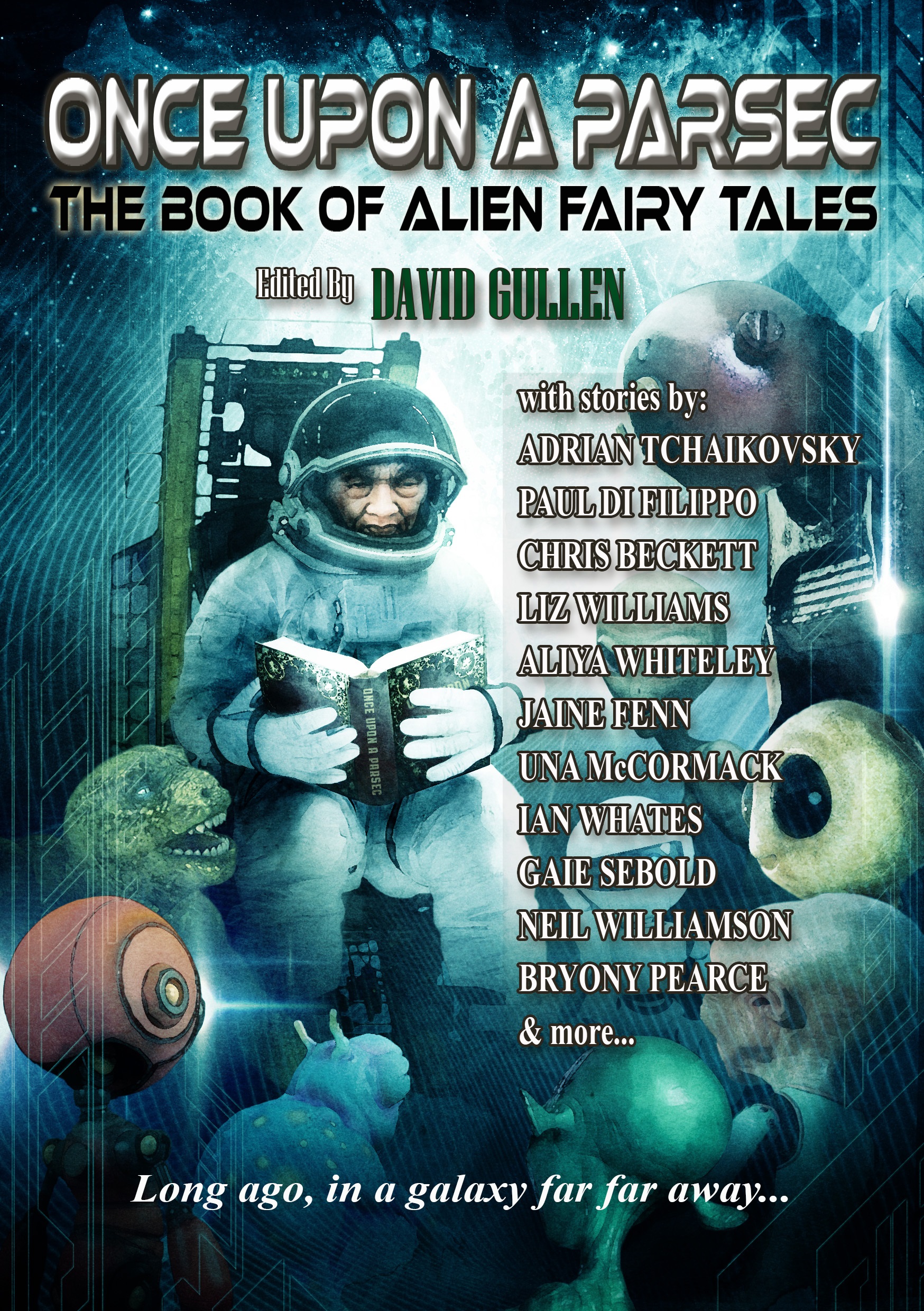

In the anthology, Once Upon a Parsec, edited by David Gullen and published by Newcon Press in June 2019.

Reprinted in The Best of British SF 2019, edited by Donna Scott and published by Newcon Press, 2020.

Published as a chapbook as part of my guest of honour contribution for Novacon 48, in Nottingham.

Included in the collection 2001: an Odyssey in Words, edited by Ian Whates and Tom Hunter, published by Newcon Press, July 2018.

Published by Audible as part of Jali, a new collection of original audio SF stories, April 2018. Read by Clare Corbett.

My collection Spring Tide contains 21 stories which aren’t listed separately on this page, as they are all original to the collection:

Cellar // The End of Time // Love // The Lake // Creation // Transients // The Kite // The Steps // Frozen Flame // Still Life // Dear // Rage // Roundabout // Ooze // Newmarket // The Great Sphere // The Gates of Eden // The Man who Swallowed Himself // Aphrodite // Spring Tide // Sky

‘The Man who Swallowed Himself’ is reprinted in Stories of Hope and Wonder from Newcon Press, 2020.

Published as my guest of honour contribution to the Dortcon convention programme, 2015. (Dortmund, Germany).

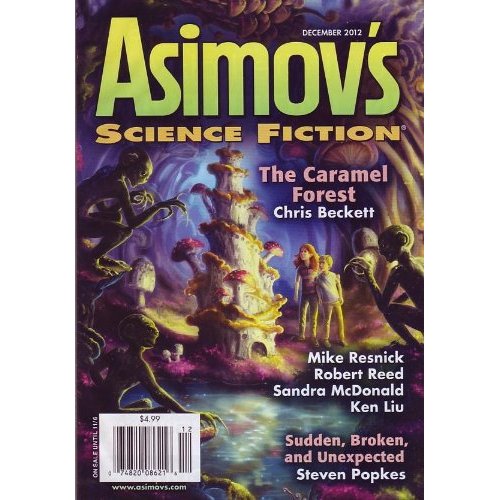

Published in Asimov’s, December, 2012.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Asimov’s, July 2011.

Humans have colonized Lutania, where Stephen works as a data analyst for the Agency. He’s an antisocial fellow who rudely avoids his co-workers and prefers the company of the simple settlers in their farming villages. His three-year gig on Lutania is nearing its end, when he’ll be transmitted back to Earth. This process necessarily involves the loss of all memories accumulated during the last 29 days before transmission. Agency rules prohibit employees from working after their Day 40, a stricture that Stephen resents and fears, for reasons he doesn’t quite articulate to himself. Or perhaps that he can’t remember. Stephen seems to have a secret from himself.

A character study of a person who lives on the fringes of normality, or perhaps further off. He has a strong aversion to the indigenes, who seem to be able to read minds; can they see the secret he keeps hidden from himself? There are some oddly idyllic scenes when he enjoys himself alone in the native Lutanian forests, but this is not where he chooses to take his enforced vacation. A very subtle horror story. I wish the premise were more credible.

Lois Tilton, Locus

Reprint:

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Postscripts anthology #22/23, ‘The Company He Keeps’, edited by Pete Crowther and Nick Gevers, 2010.

Jacob Stone is the nominal captain and sole crew member of an interstellar cargo ship that is so totally automated his job is mainly to sit alone and wait for emergencies that never happen. The job pays well because few people can tolerate the prolonged isolation, but Jacob is a misanthrope and a miser who lives only to accumulate wealth. On one stopover he encounters another solitary ship captain, a young man with a brighter future than his own. Jacob is jealous and brags about the passengers he is carrying in his cargo hold, a group of aliens on a religious pilgrimage who travel in a kind of “dry sleep” from which they are rehydrated at the end of the journey.

They were transparent too, and hard and fragile. But these were little people nearly half a metre tall, people that resembled human beings, with hands and feet and little faces. And they weren’t really empty shells either, even if they looked that way.

Jacob continues on his journey, but now he has become obsessed with the little aliens, helpless in their dehydrated stasis; he comes to hate them just because of the way the other man admired them.

The title refers to Jacob and the shriveled state of his heart, a man who cares for nothing but himself and not even himself very much. It is the banal and casual nature of his evil that makes this one effective horror.

Lois Tilton, Locus.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Conflicts anthology, edited by Ian Whates, Newcon Press 2010.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Free audio version here, narrated by Scott Barclay.

Published in Asimov’s, June 2010.

Virtual reality. Fabbro created an idyllic world and copies of himself to live in it, but the copies eventually began to get ideas of their own, and ambitions. Finally, after rebellions and wars, Fabbro has entered the world he made and Tawus has come to confront him, to justify himself.

“I used to think about you looking in from outside,” he said. “When we had wars, when we were industrializing and getting people off the land, all of those difficult times. I used to imagine you judging me, clucking your tongue, shaking your head. But you try and bring progress to a world without any adverse consequences for anyone. You just try it.”

There is more here than virtual reality. Tawus embodies the contradictions between determinism and free will, between progress and stagnation. This is the retelling of a much older story of creation and rebellion. RECOMMENDED.

Lois Tilton, Locus

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Postscripts anthology #19, ‘Enemy of the Good’, edited by Peter Crowther and Nick Gevers, 2009.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Interzone, March-April 2010. (The issue also includes a guest editorial by the author, which comments on the story.)

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

»» Read the entire story! »»

Published in Asimov’s, April-May 2009.

“Everyone wears bugeye goggles to interact with the virtual world while shutting out most of the real one. Everyone but Richard, who is not “normal.” Richard sees too many things that aren’t really there for everyone else, like Electric Man and Steel Man. He doesn’t need technology to make him see even more delusions.

Emerging from the burger bar, Richard too confronted the drizzle and the electric lights: orange, white, green, red, blue. But while Jenny had taken the everyday scene for granted, for him, as ever, it posed an endless regress of troubling questions. What was rain? What were cars? What was electricity? What was this strange thing called space that existed in between one object and the next? What was air? What did those lights mean, what did they really mean as they shifted from green to amber to red and back again, over and over again?

Richard thinks that one day he may be the only person who ever sees the world as it is, and that perhaps, if no one sees it any longer, it may cease to exist. To see atomic truths, you need to have atomic eyes.

A fascinating and humane look through a pair of different eyes, with hints from Bishop Berkeley.” – Lois Tilton, The Internet Review of Science Fiction

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Interzone, October 2008 (one of three stories, accompanied by an interview conducted by Andrew Hedgecock).

Audio version, read by Simon Hildbrandt, available here.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Interzone, October 2008.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Published in Interzone, October 2008.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

»» Read the entire story! »»

Published in Interzone, September-October 2006; 2nd place in annual Interzone reader’s poll.

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

“I’ll admit that Chris Beckett’s “Karel’s Prayer” was the one I was really itching to read, and so I left it till last, just like the Yorkshire puddings with my Sunday roast. Ah, sweet deferment of gratification – it was well worth the wait. The clever layering and deep themes are a hallmark of Beckett at his best – mixed in with the clash of science and religion are questions of identity, of knowing who and what one is. Dovetailing with current events in the news, there is torture and sneaky governments enacting backstage shenanigans in the name of national security. The very ambiguity of right and wrong is the pivot for the whole thing – comparative morality portrayed with all the warts and scars. It would be a shame to spoil this one for a reader, so you’ll just have to take my word for it – this is a brilliant story. At the risk of veering into hyperbole, Beckett may run the risk of becoming (thematically, at least) Britain’s Philip K. Dick – I say ‘risk’ only because that’s one hell of a benchmark to set for anyone. I hope he lives up to it – minus the descent into religious paranoia and insanity, of course.” – Paul Graham Raven, Velcro City Tourist Board

Published in Asimov’s, March 2006.

The back story to the novel.

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Asimov’s, December 2005.

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Interzone, May-June 2005; 3rd place in annual Interzone reader’s poll.

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Asimov’s, October-November 2004

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Asimov’s, March 2004

“From the writer’s bio we learn that Chris Beckett has been a social worker, a career that judging from “Tammy Pendant” lends a tint of gritty nastiness to one’s worldview. The title character is a problem teen caught in the ministrations of the British social service. We meet her in between foster homes, suffering the attentions of psychologists and caseworkers. Tammy is bitter and angry. She alienates everyone who might otherwise care for her. All the kids at the center where Tammy now lives know about the Shifters, a group of people who can move between worlds. Here’s Tammy’s self-defined salvation. She seduces a Shifter, steals his bag of magic pills, and takes one, only to be caught by the police and brought to the hospital to have her stomach pumped. The system, it seems, won’t let her go. Does the experience change Tammy? That would be telling. Suffice it to say that this is an excellent story with a mean streak that’s true to the very end.” – Jeremy Lyon, Tangent

Published in Interzone, February 2003

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Interzone, October 2002

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Interzone, June-July 2002

»» Read the entire story! »»

Published in Interzone, November 2001; 4th place in annual Interzone reader’s poll.

Published in Interzone, October 2001; 1st place in annual Interzone reader’s poll.

(The starting point for the novel of the same name)

Published in Interzone, October 2000

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

“I don’t often laugh out loud when reading, and even less often at stories that are not comedic. “Snapshots of Apirania” by Chris Beckett is not comedic, and it made me laugh. It is funny in a peculiar sort of way. The story is simply the monolog of someone displaying their vacation slides, from their trip to Apirania, a world somewhere else in our galaxy. The narrator is as clueless as any aloha shirted American wandering the streets of Lhasa looking for french fries. It is the tension between the scenes described in the snapshots and the narrator’s remarks on them that brings both laughter and sadness. A clever story, this is the gem of the issue.” – Jay Lake, Tangent

Published in Interzone, April 2000

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

“Simply put, this is the best time travel story I’ve ever read. The story opens on the yacht of Alex, a recent college graduate and ne’er-do-well, who has invited his friend Han on a sailing trip. They spend some time happily cruising about the Mediterranean together until Alex’s meddling father drops in (via helicopter, of course,) and gifts them with a time machine. The three of them decide to sail their ship to the sack of Troy, and join in the “fun” of the Trojan Horse. Alex, who is dubious about this whole affair from the beginning is out-voted by the exuberance of his father and his friend. One of the great things about this piece is how much it really is about Alex. Both Han and Alex’s father go through the adventure fairly unfazed, but Alex is affected very deeply by it. Things will never be the same for him, and, with luck, the reader as well.” – Lynda Moorhouse, Tangent

Published in Interzone, March 2000

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

“The writer and traveler Clancy, who has built fame and fortune on selling his accounts of foreign lands and exotic experiences to his native Metropolis, discovers that “The Marriage of Sky and Sea” may hold more wonders than even he can capture. This tale presents his attempts to construct a narrative that will be faithful to his latest trip, one to a primitive and possibly idyllic planet, while at the same time recounting those experiences directly. But unlike the dozens of times he has followed the same process before, Clancy now struggles to provide a commercially viable work that will be snapped up by the masses. His difficulties supersede the ordinary art-versus-commerce polemic, delving far deeper into his psyche and his predicament. In a delightful twist, his creative process is brought to life by his dictation to Com, his artificial assistant. Beckett’s ambitious story works on all fronts, fully rendering a complex individual, intermingling past with present, commenting on tropes like the “stranger in a strange land” or the “noble savage,” but never reducing itself to them. It’s a superlative, unexpectedly lyrical story and the perfect choice for a final piece: the ideal marriage of idea and execution.” – Alvaro Zinos-Amaro (as part of a review of The Turing Test short story collection), The Fix

Published in Interzone, March 1999

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Interzone, December 1995

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Interzone, August 1994

(This story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Published in Interzone, August 1993; 3rd place in annual Interzone reader’s poll.

The original prototype for the novel Dark Eden. (The story as first published is archived here.)

Published in Interzone, February 1992

Published in Interzone, July 1991

Prototype for the main subplot of The Holy Machine.

More about this story here.

»» Read the entire story! »»

Published in Interzone, April 1991

(A prototype for the novel The Holy Machine; this story is collected in The Turing Test from Elastic Press)

Reprints: