Published in Solaris Rising 3, edited by Ian Whates. (August, 2014)

Category: Short stories

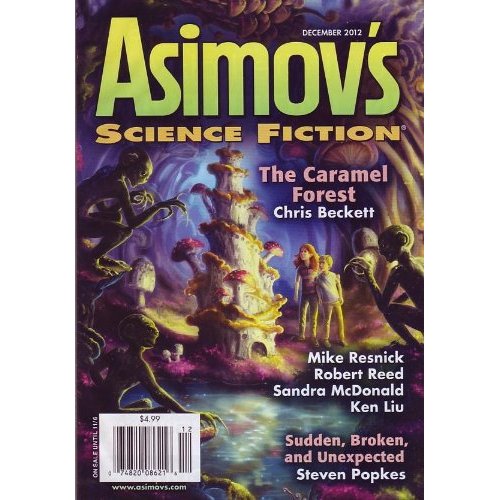

The Caramel Forest

Published in Asimov’s, December, 2012.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Day 29

Published in Asimov’s, July 2011.

Review:

Humans have colonized Lutania, where Stephen works as a data analyst for the Agency. He’s an antisocial fellow who rudely avoids his co-workers and prefers the company of the simple settlers in their farming villages. His three-year gig on Lutania is nearing its end, when he’ll be transmitted back to Earth. This process necessarily involves the loss of all memories accumulated during the last 29 days before transmission. Agency rules prohibit employees from working after their Day 40, a stricture that Stephen resents and fears, for reasons he doesn’t quite articulate to himself. Or perhaps that he can’t remember. Stephen seems to have a secret from himself.

A character study of a person who lives on the fringes of normality, or perhaps further off. He has a strong aversion to the indigenes, who seem to be able to read minds; can they see the secret he keeps hidden from himself? There are some oddly idyllic scenes when he enjoys himself alone in the native Lutanian forests, but this is not where he chooses to take his enforced vacation. A very subtle horror story. I wish the premise were more credible.

Lois Tilton, Locus

Reprint:

- Terror at the Crossroads: Tales of Horror, Delusion, and the Unknown, edited by Emily Hockaday and Jackie Sherbow

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Two Thieves

Published in Asimov’s, Jan 2011.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

The Desiccated Man

Published in Postscripts anthology #22/23, ‘The Company He Keeps’, edited by Pete Crowther and Nick Gevers, 2010.

Reviews:

Jacob Stone is the nominal captain and sole crew member of an interstellar cargo ship that is so totally automated his job is mainly to sit alone and wait for emergencies that never happen. The job pays well because few people can tolerate the prolonged isolation, but Jacob is a misanthrope and a miser who lives only to accumulate wealth. On one stopover he encounters another solitary ship captain, a young man with a brighter future than his own. Jacob is jealous and brags about the passengers he is carrying in his cargo hold, a group of aliens on a religious pilgrimage who travel in a kind of “dry sleep” from which they are rehydrated at the end of the journey.

They were transparent too, and hard and fragile. But these were little people nearly half a metre tall, people that resembled human beings, with hands and feet and little faces. And they weren’t really empty shells either, even if they looked that way.

Jacob continues on his journey, but now he has become obsessed with the little aliens, helpless in their dehydrated stasis; he comes to hate them just because of the way the other man admired them.

The title refers to Jacob and the shriveled state of his heart, a man who cares for nothing but himself and not even himself very much. It is the banal and casual nature of his evil that makes this one effective horror.

Lois Tilton, Locus.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Our Land

Published in Conflicts anthology, edited by Ian Whates, Newcon Press 2010.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Free audio version here, narrated by Scott Barclay.

The Peacock Cloak

Published in Asimov’s, June 2010.

Reviews:

Virtual reality. Fabbro created an idyllic world and copies of himself to live in it, but the copies eventually began to get ideas of their own, and ambitions. Finally, after rebellions and wars, Fabbro has entered the world he made and Tawus has come to confront him, to justify himself.

“I used to think about you looking in from outside,” he said. “When we had wars, when we were industrializing and getting people off the land, all of those difficult times. I used to imagine you judging me, clucking your tongue, shaking your head. But you try and bring progress to a world without any adverse consequences for anyone. You just try it.”

There is more here than virtual reality. Tawus embodies the contradictions between determinism and free will, between progress and stagnation. This is the retelling of a much older story of creation and rebellion. RECOMMENDED.

Lois Tilton, Locus

Reprints:

- Year’s Best Science fiction # 28, edited by Gardner Dozois

- Esli Magazine (Russian translation) See illustration here.

- Audio version, read by George Hrab on Starship Sofa here.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

The Famous Cave Paintings on Isolus 9

Published in Postscripts anthology #19, ‘Enemy of the Good’, edited by Peter Crowther and Nick Gevers, 2009.

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Johnny’s New Job

Published in Interzone, March-April 2010. (The issue also includes a guest editorial by the author, which comments on the story.)

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)

Atomic Truth

Published in Asimov’s, April-May 2009.

Reviews:

“Everyone wears bugeye goggles to interact with the virtual world while shutting out most of the real one. Everyone but Richard, who is not “normal.” Richard sees too many things that aren’t really there for everyone else, like Electric Man and Steel Man. He doesn’t need technology to make him see even more delusions.

Emerging from the burger bar, Richard too confronted the drizzle and the electric lights: orange, white, green, red, blue. But while Jenny had taken the everyday scene for granted, for him, as ever, it posed an endless regress of troubling questions. What was rain? What were cars? What was electricity? What was this strange thing called space that existed in between one object and the next? What was air? What did those lights mean, what did they really mean as they shifted from green to amber to red and back again, over and over again?

Richard thinks that one day he may be the only person who ever sees the world as it is, and that perhaps, if no one sees it any longer, it may cease to exist. To see atomic truths, you need to have atomic eyes.

A fascinating and humane look through a pair of different eyes, with hints from Bishop Berkeley.” – Lois Tilton, The Internet Review of Science Fiction

Reprints:

- Esli Magazine (Russian translation)

(Collected in The Peacock Cloak from Newcon Press)