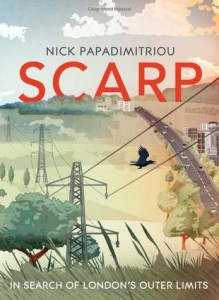

This is an odd book, an attempt to evoke a piece of semi-urban landscape which most people don’t even recognise as a geographical entity: the escarpment which runs north of London between Hertfordshire and the old county of Middlesex, which the author christens ‘Scarp’. To the north and south of it, he points out, other strips of high ground have names and identities and are seen as distinct features – the South Downs, the North Downs, the Chilterns – but Scarp is to all intents invisible. The book describes his attempts to get to know it, to get inside it, and to make it visible and tangible, trudging to and fro across it, sleeping out in it, reading about it, gathering up scraps of it, fantasising about it, studying it on maps.

This is an odd book, an attempt to evoke a piece of semi-urban landscape which most people don’t even recognise as a geographical entity: the escarpment which runs north of London between Hertfordshire and the old county of Middlesex, which the author christens ‘Scarp’. To the north and south of it, he points out, other strips of high ground have names and identities and are seen as distinct features – the South Downs, the North Downs, the Chilterns – but Scarp is to all intents invisible. The book describes his attempts to get to know it, to get inside it, and to make it visible and tangible, trudging to and fro across it, sleeping out in it, reading about it, gathering up scraps of it, fantasising about it, studying it on maps.

Scarp isn’t ‘beautiful’ like the South Downs. It is never going to be made into a national park, or find its way onto the lid of a biscuit tin. Suburban sprawl, satellite towns, sewage works, golf-courses, and major roads are flung across it, creating new, human geographical categories (towns, boroughs, motorways…) which cut across and camouflage the physical fact of Scarp. But, as the author says, ‘everywhere is somewhere’. I like this thought. Our conventional idea of communing with landscape is to leave our urban dwellings to visit ‘wildernesses’ and beauty spots. But this is limiting, perpetuating an artificial division between the human and the ‘natural’ which actually diminishes nature (perhaps rather in the way that men diminish women by reducing them to objects of desire, fantasy and idealisation).

I remember many years ago, when I lived in the hilly city of Bristol, wondering what had become of the streams and rivers that had shaped the land on which the city stood, and suddenly realising that of course they were still there. The rain still fell, the laws of gravity still applied, the same amount of water must flow across the land along the same pathways. True, the streams now ran through drains beneath the roads, but the essential machinery of the land remained unchanged.

It’s this kind of insight that Papadimitriou seeks to deepen and integrate into his understanding when he describes litter-clogged streams in concrete culverts, squashed squirrels on dual carriageways, the musty smell of abandoned industrial units… all in one and the same breath (so to speak), as he talks about wildflowers, hedgerows, sheep fields, trees and birds in flight. And this weaving together, this refusal to go along with conventional oppositions of human/natural, ugly/beautiful, spoilt/unspoilt, negligible/significant, also includes an attack on the boundary between interior/exterior, as he adds to the mix his own state of mind, fragments of autobiography, and scraps of the documented or imagined lives of people who live, or have lived, in this same landscape.

It’s a rambling book – you could even say it was a bit of a mess – and, some way into it, I wasn’t sure it was really to my taste. I suppose I’m not a natural reader for this book, in any case, as I can’t call to mind the specific places he evokes. I was also slightly irritated in the early chapters by aspects of the authorial tone: Papadimitriou, it seemed to me, was a little too self-consciously inviting the reader to see him as a sort of driven obsessive out of some JG Ballard story. (Papadimitriou himself talks about how his ‘internal balance would oscillate between the ego’s surrender in the face of a larger entity… and a desire to gain ownership and mastery of that same entity through cultural production’, and I guess that the bits that bugged me are the bits when the needs of the ego became a bit too dominant in that particular tussle). Anyway, as I read on, I stopped noticing this (and/or Papadimitriou seemed to stop talking about himself in that particular kind of way). I also stopped worrying that I was only getting a tiny fragment of what the author would have had in his mind as he described these scenes, and allowed myself to be absorbed in the project itself, tapping into my own memories of comparable places to fill the gaps and allow myself, so to speak, to join in.

It was when he described a particular rubbish-strewn piece of wasteland (a scrappy little piece of ground between two busy roads) in which he used to hide while playing hooky from school, that this book really got under my skin. I’m not aware of any place in my own past which is exactly like that, and yet this scene hit me with great force. A somewhat solitary and troubled teenager, I did play hooky from school myself, once going into hiding for several days and nights, and, during that time, I too found myself hunkering down in odd little corners, trying to entertain myself and keep myself warm beyond the gaze of the adult world. So perhaps some of those memories were what this triggered. But, for whatever reason, I had the sense that the book had somehow found a mainline to my own unconscious, the wellspring of my dreams. (In fact, reading this passage was like suddenly remembering a place that I had visited in my dreams.) After that point I was fine with whatever Papadimitriou wanted to tell me. I particularly loved the Appendix, purporting to be the journal of a hairdresser called Perry Kurland, scrawled in the pages of a Caravan Club of Great Britain logbook.

I myself am interested in landfill sites. I can’t really say exactly why, but there is something I find quite fascinating about these wide low man-made hills of refuse, usually infested with seagulls, and covered with black plastic pipes to carry away the methane from the stew beneath. I crane round to look at them when I drive past them – there is a particular fine group of them that I often pass between Bedford and Milton Keynes – and then mull over pleasurably in my mind the processes, chemical and mechanical, that must be taking place within them, and the engineering challenges that must face their human guardians. (How do they trap that methane for instance, and what do they do with it? How to they encourage the ground to settle?). Why, when you think about it, should this pleasure be any less worthy of celebration than the pleasure of watching a mountain stream, or leaves falling in autumn, or flames flickering in a fire place?