I’ve just returned from Novacon 48 in Nottingham. I’m very grateful to the organisers and members for making me so welcome. The following is the text of my guest of honour speech. (I am not a literary historian obviously, so this should be read as the impressionistic ramblings of a writer rather than as the authoritative statement of a specialist.)

ONCE UPON A TIME

Once upon a time, someone started telling stories. Not lies, which are intended to deceive, not myths which the storyteller also believes, but stories. Fiction. Made up stuff that both the story teller and their listeners know perfectly well have never really happened

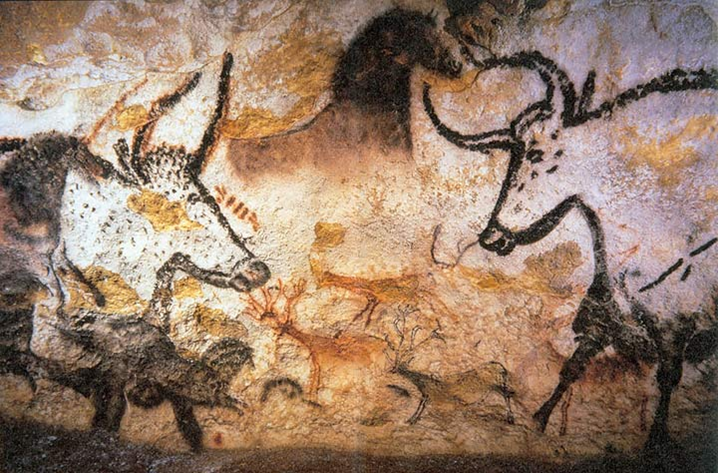

I can’t see how we could ever know for certain how or when this first occurred. I’m guessing it would be at least as long ago as the oldest representational rock paintings, which go back 40,000 years, because paintings are evidence of minds trying to evoke things that are not actually there. Perhaps it began with people embroidering real events, to a point that eventually everyone recognised the embroidery for what it was and took it as part of the fun. Perhaps it began as a kind of joke. Someone stating something that was manifestly untrue to make everyone laugh. You can make little children laugh like that to this day.

But however it happened, it must have felt incredibly exciting and transgressive back in the beginning: firstly to deliberately say things that everyone knew were not true (outrageous!), and secondly, knowing they weren’t true, to pretend to believe them (even more outrageous!). How strange, how wicked, how exhilarating! But what a breakthrough! What fun it opened up! Fun that’s kept us entertained for tens of thousands of years.

However, even though the difference between fiction and lies is that everyone knows fiction’s not true, the conceit until very recently has always been that the narrator is recounting events that actually happened sometime in the past. That’s the compact between storyteller and listener. ‘Let’s pretend that I’m telling you about stuff that really happenened.’

When the stuff is supposed to have happened might be the distant past. Or, as is commonly the case with contemporary realist novels, it might just be yesterday, in a past that is for all intents and purposes part of the present. Either way, storytellers for thousands of years have told their stories using the same grammatical constructions they’d employ if giving an account of real events that have already happened. Once there was a wicked Queen, we say. We don’t say, though it would be more accurate: In your imaginations, an otherwise non-existent wicked Queen will hopefully now appear.

And interestingly, even now, even after all this time that we’ve had to get used to the idea of fiction, stories still often come with elaborate framing narratives of one kind or another intended to explain how the narrator came into possession of the fictional facts that he or she is about to tell us: “This was told me by a traveller… I found in some old diaries in a trunk my attic and this is what they said… What I’m about to tell you happened to me in my old seafaring days…”

We tell stories about the story in other words. We create additional layers of fiction in order to make the fiction seem less fictional, and to bolster the pretence that a story is something that’s really happened. And, as readers or listeners, we notice inconsistencies in this story about the story? “How could the narrator have known that?” we ask, and, if there is no satisfactory answer, the story is slightly spoiled for us, we feel a bit cheated, rather in the same way as we feel cheated if, having read right through an exciting narrative, we are told at the end that it was only someone’s dream. Why should these things matter to us, we might ask, when we knew the whole thing was made-up anyway? But they do. Fiction works because we let ourselves buy into the idea that what fiction pretends to be, it really is: an account of something that has happened. And we want it to rigorously maintain that pretence.

THE INVENTION OF THE FUTURE.

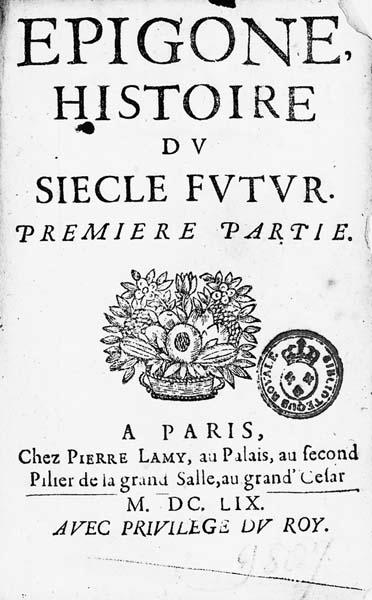

But then, 359 ago, a book was published – Epigone, by Jacques Guttin– that described itself as ‘a history of the future century’. A story about things that not only hadn’t happened, but which the story itself proclaims in its title not to have happened . It was a pretty odd story, from what I gather, and certainly no masterpiece, but (apparently) it was the first.

There were no more future stories for another seventy years, but from the mid eighteenth century –so we’re now talking less than three centuries ago- a few more future stories started to appear. Samuel Madden, an Irishman, is the author of the second future fiction, and the first (or so I understand) in English. It was a work of political satire about the threat of Catholic world domination: so a sort of DUP dystopia. L’An 2440 was another eighteenth century future story. This very popular utopian novel was published in France in 1770, nineteen years before the French revolution.

Just to be clear, these books weren’t the beginning of science fiction. For one thing, they weren’t science fictional in a way we would recognise: they didn’t really deal with technological change or new scientific discoveries. For another, there had been tales that were in some respects science fictional a long time before these early future stories -journeys to the moon, for instance, can apparently be found all the way back to classical times- but these early space adventures had all been set in the recent or distant past in the conventional manner, and not the future.

It’s not that people didn’t think about the future before. Of course they did! Everyone thinks about the future! It’s the location of all our hopes and fears. And there had been writings about the future, in the form of speculations and prophesies for many thousands of years. The final book in the Bible, for instance, is a vision of the end of the world, and its name is of course one that we now associate very much with certain kinds of science fictional scenarios, the Apocalypse. (The word didn’t originally refer to the destruction of the world. It meant ‘uncovering’, ‘disclosure’, ‘revelation’: Revelations being, of course, the alterative English name of the same Biblical book).

So people had always wondered about the future, and people had even written about it, but until 360 years ago, no-one had thought to set a story there and it’s not until the mid-eighteenth century, less than three hundred years ago out of the, well let’s say 40,000 years of human story-telling, that there was more than one isolated instance.

That strikes me as quite a startling fact.

And yet, when you think about it, it’s not so surprising, because, as we’ve seen, the convention of storytelling has always been that we’re being told about stuff that’s happened. That this pretence is an important part of storytelling is evidenced by all those complex framing narratives, those stories about stories. And stories set in the future very clearly violate that convention. ‘Nobody can “narrate” was has not yet happened’ as Aristotle apparently observed.*

Some early future fictions got round this by describing a dream or vision that the narrator had had, or which the narrator had heard about: this device was used in Mercier’s 2440 for instance. Since the vision or dream has already supposedly happened, it can then be narrated in the past tense in conventional fashion. (This is also the technique used, by the way, by the book of Revelations, which purports to describe a vision experienced by John of Patmos. Since the Bible presents itself to us as fact not fiction, it really does need an explanation for how it can tell us stuff that hasn’t yet happened. The pagan Norse equivalent, the story of Ragnarok, the Last Battle, as presented in the Icelandic sagas, has a similar kind of framing narrative: it’s a prophesy made to the god Odin by a woman gifted with foresight.) Other devices for getting the future back into the good old-fashioned past include time travel: for instance, Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century purports to be based on documents brought back by an angel from the future into the narrator’s present time. By talking about the contents of the documents which he’s read, he can preserve the traditional story-telling convention.

But anyway, whatever the devices used to make it palatable, this curious conceit caught on, this new kind of story which pretended that the future had already happened and made it a setting for stories, satires and utopian or dystopian imaginings. And, as we know, it’s moved in three and a half centuries from being an odd little one-off to becoming the mainstay of a whole rich genre in the C19th, C20th and C21st, a genre which gets its own section in bookshops, its own specialist bookshops even, and is the subject of conventions such as this.

Now of course even today, science fiction isn’t necessarily set in the future. It can be set in the past, or in the present. It can be set ‘in a galaxy far far away’ whose location in time is irrelevant. It can be set in a parallel timeline, as I myself did with my novel Marcher. But, although I don’t know the exact percentage, I’m sure you’ll agree that 95% at least of contemporary SF is set in the future.

And these days science fiction readers are sufficiently acclimatised to this notion these days as to no longer require devices such as visions or dreams or time machines to account for the fact that the narrator is telling us in the present about events that no one in the present could possibly know about. We’re used to it now.

But imagine you’re not used to it, for a moment, and think about the breakthrough that future fiction represented.

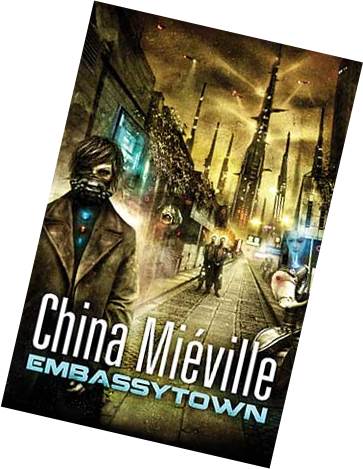

I spoke earlier about how fiction itself must have seemed rather exciting and transgressive when someone first came up with it. Everyone pretending something had happened when they all knew it hadn’t! (I think of those aliens in China Mieville’s Embassytown, and the maddening, addictive, thrill they got from the idea of saying things that weren’t true). Well, it seems to me that futuristic fiction actually represents another whole level of transgression, in that it involves an additional layer of untruth, and the violation of an ancient convention about what a fictional story should pretend to be. When you bear in mind that it apparently took tens of thousands of years of made-up stories before anyone thought of setting fiction in the future, you realise just what a big step it was, and the scale of the transgression involved. Transgression not in the sense of a crime, obviously, nor in a moral sense, but in the more literal sense of stepping over a boundary. And actually, I think we’ve all experienced this for ourselves. Looking around the room, I don’t think there are all that many people here who would have been around in the seventeenth century –or even the eighteenth, to be fair– but probably most of us started out in life being told stories set in the past in the traditional manner, and only at some later date encountered the idea of a story set in the future. So in a way we’ve all been through the same trajectory, as it were in microcosm. Probably you can remember the first time you encountered a story set in the future and what it was?

And actually, I think we’ve all experienced this for ourselves. Looking around the room, I don’t think there are all that many people here who would have been around in the seventeenth century –or even the eighteenth, to be fair– but probably most of us started out in life being told stories set in the past in the traditional manner, and only at some later date encountered the idea of a story set in the future. So in a way we’ve all been through the same trajectory, as it were in microcosm. Probably you can remember the first time you encountered a story set in the future and what it was?

I remember finding the idea rather strange and thrilling when I first encountered it. And, in a good way, rather eerie. You too?

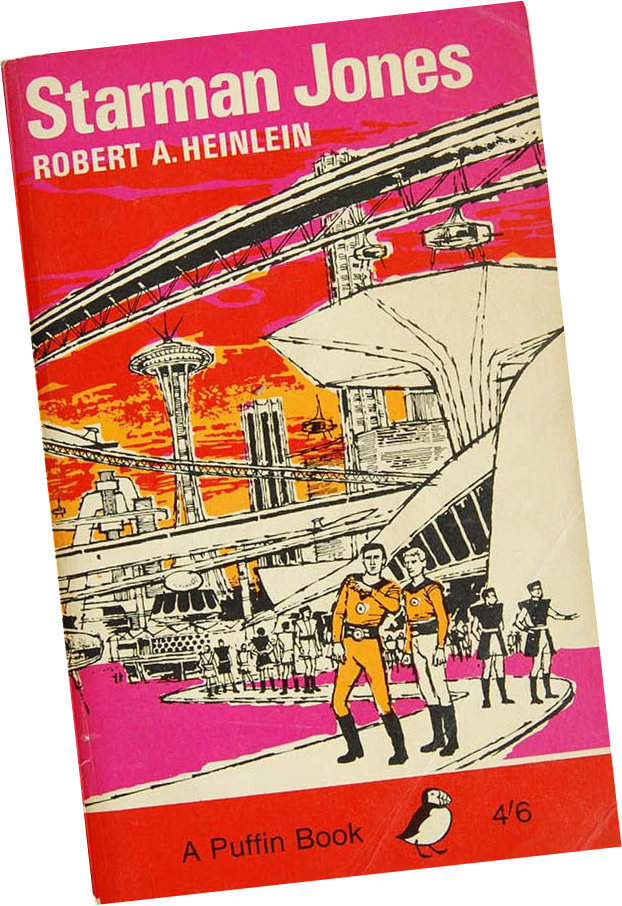

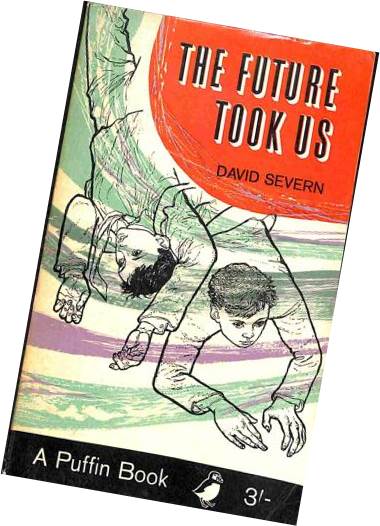

The first future novels I encountered by the way were: Heinlein’s Starman Jones, which, I now recall, involved starship navigators, or astrogators, who depended on actual printed tables collected in physical books to find their way through space warps, and The Future took Us, which involved a rather scary and convincing dystopian future in which maths was prohibited and anyone who made any kind of wheel was condemned to death by being tied inside a metal wheel and rolled down a ramp into a lake. (The Future took Us, incidentally, had one of those framing narratives involving time travel, so as to allow the narrator to be someone in the present describing an experience in his past.)

Thinking about those books now, and about the books in my father’s science fiction collection which I then went on to devour, I feel a little sad. I wish I could get back the feeling of my first exposure to stories set in the future. There really was something transgressive about it. Something dangerous.

Thinking about those books now, and about the books in my father’s science fiction collection which I then went on to devour, I feel a little sad. I wish I could get back the feeling of my first exposure to stories set in the future. There really was something transgressive about it. Something dangerous.

So yes, we forget, I think, just how truly revolutionary it was to tell stories set in the future, and discard the narrative conventions of 40,000 years. Indeed, a lot of people are still not comfortable with the idea of future stories to this day. I’m sure you have people among your friends and relations who can’t abide the idea. I certainly do.

DOUBLY INVENTED

And actually, in spite of having made this extraordinary leap, future stories still haven’t completely abandoned the old rules of narrative time, for almost all stories set in the future are written in the past tense (or maybe occasionally the dramatic present), thus maintaining the pretence, in a formal sense at least, that the narrator is telling us things that, from her or his point of view, have already happened. A science fiction novel written entirely in the future tense would feel very strange, wouldn’t it?

The Consul will wake up with the peculiar headache, dry throat and sense of having forgotten a thousand dreams which only periods in cryogenic fugue could bring. He will blink, sit upright on a low couch, and will groggily push away the last sensor tapes clinging to his skin. There will be two very short crew clones and one very tall, hooded Templar with him in the windowless ovoid of a room. One of the clones will offer the Consul the traditional post-thaw glass of orange juice. He will accept it and drink greedily.

‘The tree is two light-minutes and five hours of travel from Hyperion,’ the Templar will say, and the Consul will realize that he is being addressed by Het Masteen, captain of the Templar treeship and True Voice of the Tree. The Consul will vaguely realize that it is a great honor to be awakened by the Captain, but he will be too groggy and disorientated from fugue to appreciate it.

All I’ve done here is change the tense in this extract from Dan Simmons’ novel Hyperion from the past to the future (reflecting the book’s setting in the 29th century), but I think you’ll agree it sounds odd. Although you and I know perfectly well that this is a made-up story set in a future that will never really happen, nevertheless the future tense jars on the ear, because it constantly invites and re-invites questions like ‘How does the narrator know this?’ ‘What special powers does the narrator have to be able to predict or control events to such a degree?’ and even ‘Who is the narrator, and what point in time is the story being told FROM?’ (a question which a conventional past-tense narration doesn’t prompt us to ask to the same degree, unless we are given clues that the narrator is unreliable in some way, or is themself a character in the story.) In fact, I’m pretty sure that if I read a story that was written in the future tense like this my brain would still try and find a way of making these events be in the narrator’s past in the traditional fashion. (Perhaps the narrator is looking back to a point before the action, and is anticipating from there what they know is to come?)

Told in the future tense, in other words, the story about the story feels all wrong, and so we still tell future stories in the past tense. Which, when you think about it, is quite an odd combination. Grammatically the story tells us that the events described have already happened, while at the same time it tells us semantically that these events have actually not happened. These people we’re being told about haven’t even been born yet. These events won’t happen for decades, or centuries, or millennia.

None of this really matters of course. What I’m talking about is just a story telling convention like any other. And yet, maybe it’s just me, but it sometimes bugs me a bit, and I suspect it may be one of the things that put some people off the idea of future fiction. A fictional past is a made-up thing, but a fictional future is kind of doubly made up. Not only is it not true (like all fiction), but even if it were true, we couldn’t possibly know about it, however much we disguise that fact with the past tense. No matter how plausible the story might be, in other words, there is no plausible story about how the story came to be known.

And of course in a future story, unlike a novel with a contemporary setting, or a historical novel, it’s not only are the characters that are made up, but the world in which it takes place. So a future story is doubly made up in that sense too. To me as a writer, that’s a huge advantage because of all the thought experiments it allows me to engage in. But I know that for some people it’s taking invention too far.

WHY THE FUTURE?

Let’s leave that aside, though. A larger question is why, after all those tens of millennia of story-telling, did human beings, less than four centuries ago, finally start telling stories set in the future, apparently for the first time?

Well, a major reason, I’m sure, is to do with the allure of the exotic and the strange, and where we imagine they can be found.

For a very long time there have been two kinds of stories: (a) more-or-less realistic ones: those set in an everyday environment familiar to their listeners and (b) fantastical ones, deliberately set in environments which are strange and different to the one known to their listeners.

(When I was a child I had a strong predilection for the latter, which I guess is true of a lot of people here. I could never see the point of those stories which were just about kids going on a camping holiday with their mum and dad and their dog getting stuck in a cave or something. You know the ones? Dog stuck in cave stories? If some well-meaning adult gave me a book like that, my heart would sink. But if the cave turned out to lead to a goblin kingdom, or a gateway to another world, well, that different matter. )

When did fantastical story telling start? We’ll never know that either I suppose, but cave art depictions of imaginary beings like human-animal hybrids can be found going back to the Late Stone Age. (Come to think of it, I suppose this too was a major breakthrough in storytelling, another transgression: not just making up stories about humans and actual animals, but making up stories about imaginary beings that no one had ever seen.)

In any case, whenever it occurred, we know that, long long before anyone thought of future stories, there were fantastical stories. And traditionally there were several ways to provide suitably fantastical settings, one of which would be to set the story in some strange or faraway place. After all, until very recently, wherever you happened to be, most of the planet Earth was very strange and faraway indeed and much of it completely unknown.

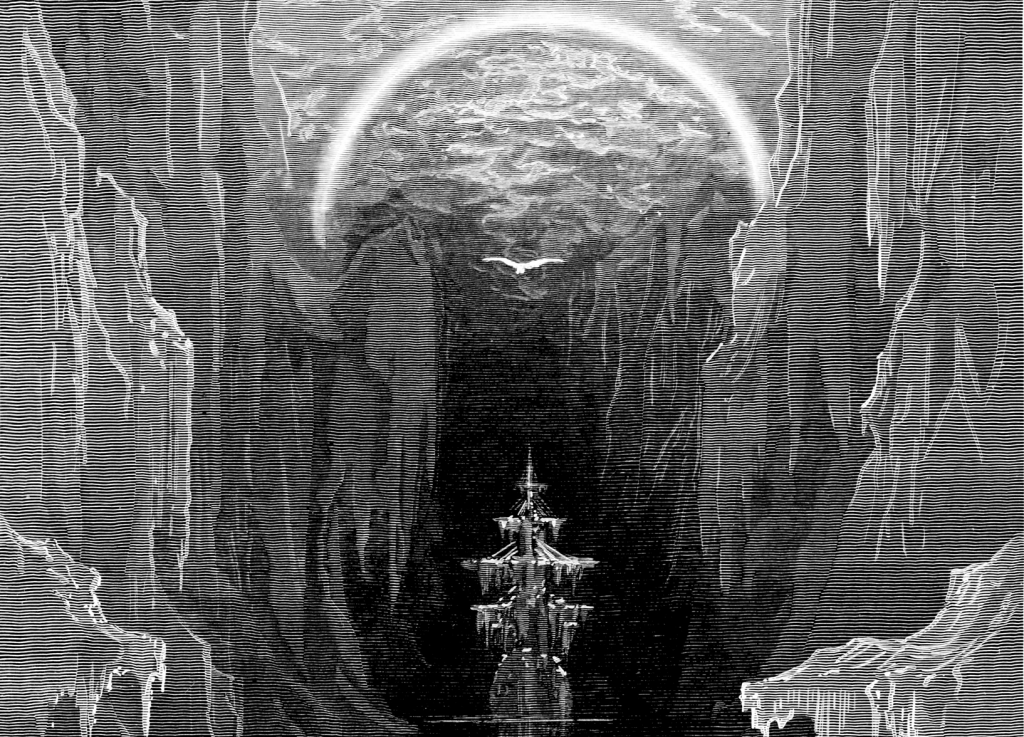

So there was plenty of scope right here on Earth for strangeness and mystery and a sense of wonder. No one had ever even seen the continent of Antarctica, for example, right up until the C19th. It was more remote and unknown then than the moon or Mars is now, making the Antarctic ocean a suitably strange and unearthly setting for Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner written at the end of the C18th. But, as we’ve seen, even in ancient times, exotic settings did also include the moon itself.

A second strategy is to set your story in the remote past. (I suppose the past is always a bit magical and ghostly, isn’t it, because of the nature of memory? And the past beyond anyone’s memory even more so, particularly in a time before photography and printing and the other technologies that allow us to preserve a detailed record.) A third strategy is to include magical/supernatural elements. In fact strategies (2) and (3) are typically combined as for instance in the stories of King Arthur and his knights, which were set by medieval story tellers in the doomed kingdom of Logres which had supposedly fallen many centuries before.

The Kingdom of Logres wasn’t geographically very far away from the French and German writers who made up the story of the stories grail, the round table and all the rest of it, and it presumably has at least some historical basis as a former Celtic land in some part of what is now England. (To this day England is Lloegr in the Welsh language: When I cross back over the Severn Bridge after a trip to Wales, I rather like being welcomed back to Logres). But of course these stories are what we would now call ‘fantasy’ and include, not only entirely invented characters, but magical and miraculous things like stones floating on water, and Dolorous Towers, and dragons, and mysterious boats that move without anyone rowing or steering them.

Something to note here is that, while the Arthurian romances were nominally set many centuries in the past, their medieval authors, such as Chrétien de Troyes (the creator of Sir Lancelot) assumed that, in terms of technology and political institutions, things in the Kingdom of Logres were much the same as in their own time. Kings, castles, chivalry, armoured knights on horseback who jousted with lances and fought with swords. Just like the twelfth century when these stories began to be written for the entertainment of real life knights.

Although I’ve said that these stories were what we’d now call ‘fantasy’, they were in this respect very different from present-day Tolkeinesque fantasy fiction, even though the latter ostensibly adopts the same strategy of setting tales of magic in a mythical past. Because of course Tolkeinesque fantasy does not include modern technology. In fact the classic fantasy novel reverts to exactly the same kind of technology that was known to de Troyes: horses, swords, kings and so on… There are doubtless a number of reasons for this, but one is (I suggest) that, these days, we know quite well that, in the past, things were different.

And this is key. In the middle ages, people could reasonably assume that the past was in many respects pretty much like the present. And, by the same token, they could also assume that the same would be true of the future. I don’t mean by this that they thought nothing would change. Of course people knew things would change in the future, and could change very drastically indeed: the fortunes of individuals and kingdoms would wax and wane, plagues and famines could wipe out half the population, invasions could turn the world upside down –life was a precarious thing back then– but these changes would be we might call first order changes rather than second order ones. Unpredictable events would happen, but the overall framework would remain much the same over long periods of time, with the same sorts of technology, the same kinds of institutions, and broadly the same understanding of the world.

Thus, for instance, medieval readers of the Old Testament, set perhaps two millennia before their time, would still find in its pages a world which in many respects wasn’t so very different from the one they knew: horses and carts, bows and arrows, ploughs pulled by oxen, patriarchs who measured their status in land and livestock … and so on.

And, if characters from the Old Testament could have somehow been transported two thousand years forward to medieval times, the same would apply. The world would look very different to them of course, in all kinds of ways, but they wouldn’t find many things that they didn’t recognise at all, or whose workings they couldn’t understand on the basis of what they already knew. (I’ve been trying to think of a medieval technology that these Old Testament time travellers wouldn’t recognise at all: all I can come up with is windmills and watermills.)

So, until comparatively recent times, people certainly had many reasons to fear the future, but they had no reason to think that the nuts and bolts of life would be much different in the future from how they were now. And that being so, why would you set a story in the future? Even if you wanted to write a thoroughly fantastical story —about a journey to the moon for instance, or an encounter with an imaginary monster— there would be no advantage in setting it in the future, as opposed to the normal arrangement of setting it in the present or the past. I don’t think we would bother setting novels in the 29th century, would we, if the 29th century looked like being pretty much the same as the 21st?

But when Guttin’s Epigone appeared in 1659, things were changing. The reformation had occurred, the monolithic authority of the Roman church had been overturned in England and elsewhere, the English Commonwealth had (temporarily) abolished the monarchy, science was beginning to question a view of the universe that had been accepted orthodoxy for many hundreds of years. I’m guessing that it began to seem possible that, given that things had changed a lot in the previous century, things in a century’s time could be substantially different again.

And as time went on, science took hold, new technologies emerged, political revolutions occurred and a moment came when the world of the present century really was so obviously different from the world of the previous century that the next century could reliably be anticipated to be very different again. I’ve noted that figures from the Old Testament would still recognise most of what they saw if a time machine carried them forward two millennia to medieval times, but take someone from medieval times and bring them forward the very much shorter time –a few hundred years– to the nineteenth century, or the twentieth, or the twenty-first, and it’s an entirely different story. Imagine a medieval time-traveller faced for the first time by a steam engine, never mind television and cars and jumbo jets. Never mind computers, and satellites and the world wide web.

In a context of rapid technological and social change, the future ceases to be a rather odd and perverse place to set a story in and becomes a rich seam to be mined for exotic locations – in some ways a much more promising one than the past, because no one knows what’s really there.

So one reason for the birth of future stories three centuries ago, is that, at about that point in history, the future began to be a promising location for fantastical stories. A lot of future stories, after all, are not serious attempts to imagine what the future will be like. They use the future setting simply for the freedom it gives to make things up, and deliver new scenarios and bear pretty much the same relation to the real future, as the Odyssey, or the Arthurian romances bear to the real past.

But there’s a lot more to future stories than that, and I don’t think the freedom to make up exotic locations is the only reason why we tell them.

Before I get to that, though, a short diversion. A word about MAGIC.

MAGIC

Being set in the future is not in itself a defining characteristic of SF, since SF doesn’t have to be set in the future. No, the defining characteristic of SF is that, (a), it introduces something new into the fictional world, and (b) this new thing is explained in terms of science or technology, rather than in terms of magic, the supernatural, or religion. At the about the same time that people started writing about the future, people were also increasingly explaining the world in terms of science and technology rather than in terms of religion. (And incidentally, a shift was just beginning to happen away from religious notions about salvation and damnation in the afterlife, towards a more modern conception of salvation and damnation in this world: progress towards a better society, or collapse into dystopian nightmares.)

Now we’re all familiar with Clarke’s third law ‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.’ I’d add to that that any form of magic that actually worked would in fact be technology. So, for instance, if Gandalf really existed, and his spells really worked, you would in principle be able to sit him down and ask him how they worked. Assuming he was willing to tell you, he’d presumably give you an explanation in terms of the interaction of certain forces, or the behaviour of invisible beings, or the existence of other worlds or dimensions which, for reasons he could presumably set out, spells and incantations are able to influence.

In other words, he’d explain things in terms of the relationship between actual, empirically demonstrable, entities, meaning that his explanation would cease to be ‘magic’ and become science and technology. In terms of what it does, a palantir is not so different from a video phone, the main difference being is that we have no idea how it works.

And, thinking about this while writing this talk, it occurred to me what an extraordinary and marvellous thing it is that humankind stubbornly persisted in believing in magic for all those thousands of years. Because it means that, far far in advance of anything we’d now call science or science-based technology, human beings had made up their minds that the universe contained forces that were invisible but were in principle knowable, and could in principle be harnessed and used as a source of power. As a supplement to Clarke’s 3rd law, I therefore propose Beckett’s Law:

Magic beliefs and practices are not the opposite of science, but on the contrary, represent a dogged commitment to the idea that science is, in principle, possible.

So, for instance, we don’t know what magical or sacred purposes were served by Stonehenge, aligned as it is with sunrise at the summer solstice, but, given the colossal undertaking that it represents, it’s a particularly striking example of the extraordinarily tenacious leap of faith which was necessary for the emergence of science.

It’s no coincidence that early science was entangled with magic –chemistry with alchemy, astronomy with astrology– because once you’ve got hold of the idea that there is something to look for, in the structure of matter, or in the stars, you are so much closer to finding it, than you would be if you had no sense that there was anything there to be found at all.

In my Eden books, the descendants of modern humans are stuck on a planet without tools or technology of any kind.

Putting myself in their position, I asked myself how well I’d do. For instance, as a modern human, I obviously know that there’s such a thing as metal. I know it comes from certain rocks, which –I’m guessing– tend to be rusty coloured in the case of iron ore and greenish in the case of copper ore, and perhaps –and now I’m really guessing– whitish in the case of lead? I’ve no idea what tin ore looks like, though I know I’d need it for bronze. I have no idea where to look for any of these rocks, other than trial and error, and I have only the haziest idea how to extract the metal from them (crush up the rocks and make them very very hot). And, given the effort involved, and the number of times I’d have to try, and the difficulty of making a fire that was hot enough, I’d probably be stuck with tools made of things like stone and wood all my life, as is the case for the Eden people for many generations. I mean: suppose you spend days breaking up some promising looking reddish rocks, more days constructing a huge fire, and then you throw the broken rock in it, and still no metal appears in the ashes. What does that even tell you? Does that mean you’ve got the wrong rocks? Or does it mean that the fire wasn’t hot enough? Or does it mean there’s some other vital part of the process that you’ve missed completely? When you’ve got to hunt and forage to keep yourself alive, how much time would you have to try to narrow down the possible answers to these questions?

But the idea of metal is kept alive on Eden, that’s the important point. And this, for all the difficulties I’ve just described, gives the humans on Eden a vast advantage over their Palaeolithic ancestors on Earth. Yes, it might still take might take them many generations, but they’d surely discover metallurgy in a tiny fraction of the time that it took the first time round, simply because they’d believe there was something to be found.

Well, it seems to me that, in much the same way, magical beliefs kept alive the idea that the universe had a hidden structure which could be unlocked to become a source of power, and thereby made the eventual emergence of modern science possible.

And, come to think of it, that is one of the functions of science fiction too: keeping alive possibilities, even if we don’t have any idea how to realise them in fact. Prophesies and stubbornly held beliefs really are to some extent self-fulfilling. Perhaps, in John the Baptist-style, future stories help prepare the ground for the real future. Clarke’s second law isn’t quite so well known as the third: ‘The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.’

WHY THE FUTURE? (continued)

But, to return to the subject of why stories about the future became so prevalent, I’ve suggested that this is partly because, once you get hold of the idea that the future is going to be very different indeed from the present, and that we’ll be able to do things then that we can’t begin to do now, it offers starts to offer very exciting possibilities for storytelling, arguably more exciting ones than stories about a mythical past, or imaginary countries. After all, when it comes to imagined future worlds, who’s to say they won’t come true?

I’ve also just suggested, in what on reflection wasn’t really that much of a diversion, that telling stories about a strange and different future, may serve the function of helping that future come into being. Perhaps Mercier’s 2440 helped in some small way to make the French revolution happen, simply by planting the idea that a future society might not necessarily be like the one that existed at the time it was written. Or, to give a trivial example, would mobile phones have come along when they did, and in that particular form, if it wasn’t for Star Trek?

But there’s another aspect to this. The future is a worrying place. It’s a door we have to open, whether we want to or not, without knowing what lies behind it. In the Aymara language, spoken by over a million people in Bolivia and Peru, people refer to the past as being ahead of them, and the future as behind. This seems odd, given that Aymara speakers presumably face towards their destinations the same as everyone else, and have their backs turned to their starting out point, but it encapsulates a truth. We can see the past. Like a landscape spread in front of me I can see my whole life up to now, stretching out to the far-off years of my early childhood in the late fifties. And more distantly I can also see the first half of the twentieth century before I was born, World War 2, World War 1… the nineteenth century…the middle ages… the days of the Romans. In fact, I can even dimly make out a world before human beings existed. But the future I can’t see, whether it’s my own future or the future of the world. The future is like a something standing so directly behind me that I can’t even catch a glimpse of it out of the corner of my eye.

That being so, the future has always been a source of anxiety, and in some respects much more so for our ancestors than it is for us, for in the past the risks of losing your children, dying young, starving, or being invaded, were much greater in this country than they are now. (In some parts of the world, of course, all those kinds of danger are as menacing now as they ever were). And one thing that human psychology and human culture alike expend a huge amount of effort on, is managing anxiety. Much of superstitious and religious practice is intended to help stave off bad luck in the future and bring good luck. Charms, amulets, prayers, sacrificial offerings, pilgrimages to holy places… all of these things aim to enlist supernatural forces to reduce the chances of there being something nasty behind that door, or increase the chances of something nice.

(I think our modern superstition, by the way, is to place a completely unrealistic faith in the ability of professionals to predict and prevent bad outcomes. In premodern times an earthquake might have been blamed on an angry deity who had not been sufficiently appeased, but after the earthquake in L’Aquila in Italy in 2009, vulcanologists were charged with manslaughter for failing to give adequate warning.)

The future was already a worrying place, back when the main concern was what I’ve called first order hopes and fears: things that were known and familiar, even if unwelcome, like getting ill, or losing your children, or not having enough to eat. But in our era of very rapid social and technological change, there are also second order changes to worry about. I was born at the end of 1955, and in my lifetime, the world has faced threats and challenges that no one had even heard of, even as recently as my parents’ childhood: nuclear war, runaway global warming, catastrophic acidification of the oceans, vast global migrations (and the nativist backlash against them), threats to the idea of objective truth from new digital technologies, surveillance on a vast scale…

(Jeremy Bentham imagined a Panopticon, where prisoners could be watched continuously from a central point. Orwell imagined TVs which would constantly watch you and couldn’t be turned off. But no one predicted surveillance systems run by a handful of global corporations that were so seductive that we’d all willingly sign up to them!)

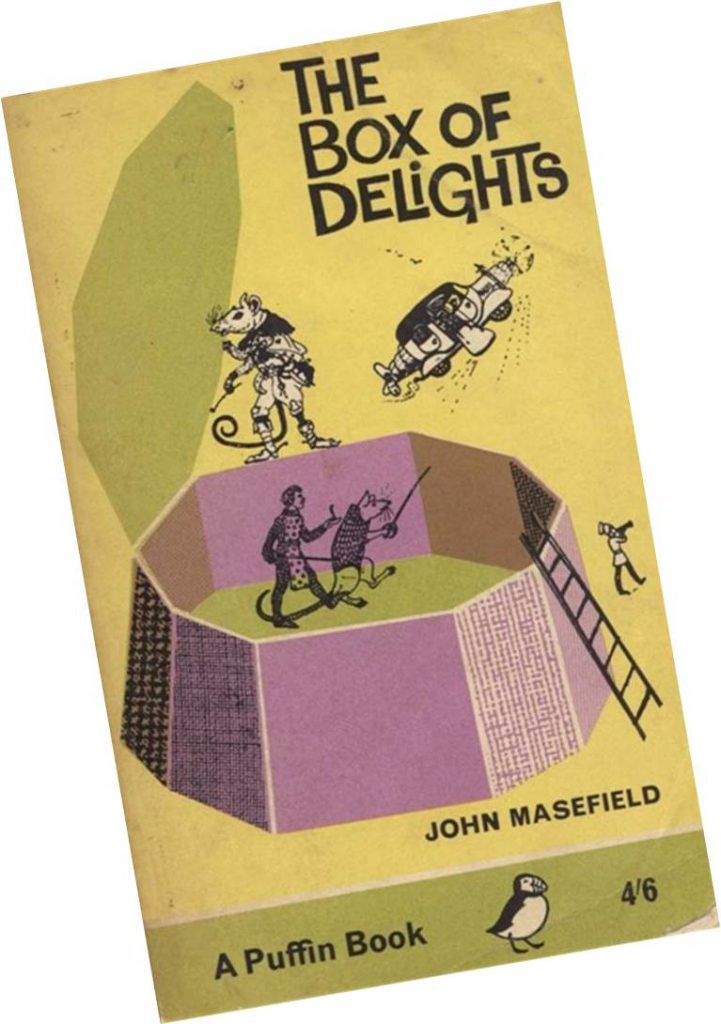

Of course there are new opportunities as well, I’ve seen extraordinary developments in my lifetime which would have been seen as fanciful science fiction even half a century before, and have been regarded as pure unadulterated magic only a couple of centuries ago. People have told stories about trips to the moon since classical times, for instance, but when I was 13, three men really went there. When I was eleven years, a human heart was successfully removed from one person and sewn into the body of another. I could go on and on. And there are minor miracles much nearer to us. As a child I was enchanted by John Masefield’s Box of Delights but right now in my pocket I carry a real-life box of delights, which would have utterly amazed me. It’s the size of a slim pack of cards. It can tell me where I am on a map and give me directions to my destination in a human voice. It allows me to speak to and see the faces of people all over the world. I can ask it questions, and it will answer. It can play games with me, any one of hundreds of them. It holds an entire library of books for me to read. It can search a vast global archive of human knowledge whenever I want to know something…

And there are minor miracles much nearer to us. As a child I was enchanted by John Masefield’s Box of Delights but right now in my pocket I carry a real-life box of delights, which would have utterly amazed me. It’s the size of a slim pack of cards. It can tell me where I am on a map and give me directions to my destination in a human voice. It allows me to speak to and see the faces of people all over the world. I can ask it questions, and it will answer. It can play games with me, any one of hundreds of them. It holds an entire library of books for me to read. It can search a vast global archive of human knowledge whenever I want to know something…

And by now you may be thinking, yes, Chris, we have heard of smartphones. But that’s my point. How quickly we get used to these things! How quickly they cease be magical and become mundane. As all conjurors know, magic is only magic when it seems impossible. (Which, incidentally, is why I think those people who want to live their lives on Mars are crazy. I give them a week or two before the novelty wears off and they realise they are stuck in a lifeless desert forever with nothing to do, nothing to look at but dust and stones, and just a handful of increasingly desperate people to talk to.)

So. Terrifying new threats, a constant cascade of novelties and discoveries, vast political upheavals… and, at the same time, the knowledge that the breakneck speed of change continues with no sign of abating: This is the world we live in. And I think one of the more profound reasons for needing future stories is that we’re haunted by the future, and we need some way of dealing with it.

I remember going through a phase as a small child in which the threat of bombs from planes in the sky became a real and constant source of dread for me. But at the same time those same planes became a source of fascination for me. I made my own pretend aeroplane controls and played at being a bomber pilot, I studied books of warplanes, I drew fighters and bombers with their wings bristling with guns and rockets. How terrifying those machines were, but yet how utterly cool! I’d made my fears into playthings. (Ballard nailed this particular kind of fascination, I think. The way we learn to love the things we most fear.)

Now, I’ve heard it said that Palaeolithic hunters painted pictures of animals in the belief that by capturing their images, they could in some way control them. I don’t know how we can really know this, but it makes perfect sense to me psychologically. To control things we try to contain them. And if we can’t contain them in physical fact, then we contain them in pictures, in stories, in theories and representations of one kind or another, even including, I think, scientific explanations: I think we look to professional experts of one kind or another not just to explain things to us but above all to reassure us that things can be explained.

Sometimes, when I go to the art show at a science fiction convention, it strikes me that I’m looking at our deepest fears and longings laid out more explicitly than you will see almost anywhere else. The art show here is very gentle, as it turns out, but I remember coming out of the art room at the Worldcon in Helsinki, feeling in need of therapy! It’s a wonder we can bear to look at some of those pictures at all, I thought at the time –ruined worlds, humans intermingled with machines, hideous technological tortures– and yet somehow the picture frame, the art show, the convention, contains them, and makes them manageable.

And I suggest that when we tell stories set in the future –a place we can’t really see at all– and tell them in the past tense as if they had already happened, it provides reassurance to our deepest and most irrational inner selves. Indeed SF novels often do include characters who are conspicuously at home in their imagined future worlds, allowing us to vicariously experience their mastery of their strange environment, just like the childhood me pretending to be a bomber pilot, so I could feel like the agent and not the victim.

Us science fiction people have a certain reputation in the rest of society as being geeky escapists not quite up to the real world. And, unfair as that is, I have to admit that if I look at myself, I can see that in my case the stereotype isn’t entirely without foundation. I am someone who finds the here and now a bit much and likes to retreat into my own head, as perhaps some of you are too. But paradoxically, even if there is some truth in the stereotype, science fiction people also face a lot of things that other people prefer not to even consider.

THE FUTURE OF THE FUTURE

A few final thoughts. We are now living in an era that once was itself once the setting of future fictions. The twentieth century brought us moon landings and atom bombs, along with less flashy but arguably far more important developments such as penicillin and reliable contraception (the latter being one of the most revolutionary technological changes in history, I personally think, in terms in its effect on human society). But now the twentieth century is in the past. 1984 has been and gone. 2001 was 17 years ago, and yet we’re still writing future stories, 360 years on from when they first started.

The future isn’t what it was, I don’t think. There’s nothing on the horizon now to take the place that was occupied by space exploration and jet planes and the atom bomb in the mid-twentieth century. Nothing with quite their unspeakable glamour. Back in the twentieth century, many of our future stories assumed that the future would simply be an extension of the past, with the human race, having conquered the whole of planet Earth, spreading out beyond it –hence space opera with its vast empires and its wars– but I think by now we ought to be facing the fact that, if not for everyone, then for almost everyone, our future, for better or worse, will be confined to this one planet for a very long time and quite probably forever. (Starships are possible –we know that– but perhaps not starships that could carry thousands, of people, however useful such machines may be for story-telling purposes?)

Here on Earth, we face as many threats as ever, many of them created by the very technologies that first opened up our modern conception of a future as another, different country, and of nature as a thing that could be unlocked and mastered. And yet the technologies we will need to meet those threats are not necessarily technologies of the glamorous kind that are easy to write stories about. Wind turbines, batteries, biodegradable packaging, sustainable agriculture: they’re hardly the stuff of adventure.

Many recent and new technologies now on the horizon, it seems to me, are neither glamorous nor very useful: solutions to problems that we didn’t really have in the first place, and entirely irrevelant to the real threats that beset us. Smartphones are compulsive playthings, yes, but how much have they really improved the quality of our lives? (And why on earth do we need self-driving cars? Is there some sort of world shortage of drivers that has somehow passed me by?) As for the new technologies that do lend themselves to storytelling, they’re ones that from the very outset are morally ambivalent: artificial intelligence, bioengineering, increasingly blurred boundaries between fact and fiction.

Meanwhile science itself has moved into realms where much of it is beyond the reach of all but a few to understand. For most of the human race –including me– a kind of singularity has already happened and things are going on which we are simply incapable of understanding. There’s a kind of alienation in that. People express surprise and horror at the reaction that is currently going on across the world these days against science and reason and experts, but it seems to me to have been entirely predictable.

But for better or worse, now that the Pandora’s box of science has been opened, we live in a world that constantly transforms itself, however much many of us might like things to slow down or stay the same. Future stories are old hat now, and not currently as fashionable as they were, say, in the sixties. But, though their popularity as a source of exotic locations will no doubt wax and wane, can we really imagine a world in which no one needs stories about that dark, unknowable thing standing there right behind us where it can’t be seen?

Books consulted:

Adam Roberts (2005) The History of Science Fiction. Palgrave.

Paul K. Alkon (1987) Origins of Futuristic Fiction. University of Georgia Press.

(And thanks to Adam Roberts for pointing me in the direction of the latter.)

Notes:

* Aristotle as cited by Alkon (see above)

** England is Lloegr in Welsh, but it becomes Loegr after the preposition ‘i’, due to the language’s system of mutations. (In the same way Bangor becomes Fangor).

*** More of David’s work here. Among many other things, he did the cover for the Hawkwind album, Hall of the Mountain Grill.