There’s a lot of talk these days about a growing contempt in the world for evidence, for experts, for reason itself. It’s a real concern. Not much hope for the future if decades of meticulous scientific work on climate change can all be tossed aside by know-nothing ‘common sense’. Not much hope for a decent society if obvious lies can be uncritically accepted as true, while facts are dismissed out of hand

But another kind of ugliness that’s been coming to the fore lately is the voice that says, in effect, we smart people know best, and those thick people should just shut up and wait to be told what’s good for them. Weary, angry, contemptuous: the smartsplaining voice, it might be called.

Clever educated people who are good at reasoning, should be careful not to assume that this alone makes them right.

I remember once in my social work days, visiting a barely literate client and her saying to me resentfully at the end: ‘I suppose you’re going to go away and write this all down, aren’t you?’ However reasonable I was, however conscientious, the fact remained that my interpretation of events was going to go on the record, and hers was not.

A few years later, after a change of job, I acquired a reading ticket for the Cambridge University Library, and had the habit for a while of sitting in the cafe over there to write. As I half-listened to the people at the tables around me, academics and students coming and going with their cups of coffee and tea, I noticed that I could go all day without even once hearing a regional accent of any kind, only the distinctive drawl of the British private school system.

There’s no question in my mind that every one of those people in the library would have been much better at rational argument and far better-informed than that former client of mine in her council house three miles away. But every one of their arguments, however beautifully constructed, would necessarily be based on their own experience and what they’d read, and I’ll bet that neither their experience nor their reading equipped them to know anything about that woman’s world. (This is true of me too, incidentally, although my former job afforded me small glimpses into it.)

So when some of them become politicians, or economists, or entrepreneurs, their judgements about the world, however carefully reasoned, will take almost no account at all of what that woman feels, what’s important to her, how she imbues her life with meaning. Their judgements will, on the other hand, be very amply informed by the needs of people like themselves, what’s important to them, what imbues their life with meaning.

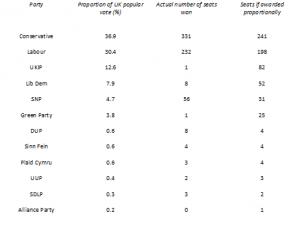

And that makes me think that what may look like a revolt against reason itself, may be in fact be a revolt against a class that is very good at reasoning, and very good at explaining why the world ought to be run in a way that suits that very same class. Not revolt against reason as such, in other words, but revolt against reasoning that (however unintentionally) is rigged in favour of the reasoners. After all, if you’re good at reasoning, you’re good at rationalising too.

Which is why I think that members of that class, including me, would do better to think about what we’ve been excluding from our view of the world, than to dismiss whole groups of people as ignorant thugs.