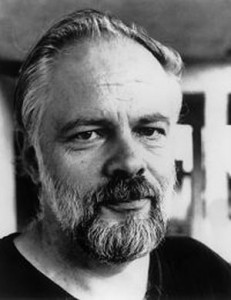

I came to Philip Dick’s work relatively late, but it has a big influence on me. I would find it difficult to say which is my favourite one of his books and stories, though at times I decide The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, which many people seem to pick, and which I may write about some other time. At other times I decide on Flow My Tears the Policeman Said, a wonderful book in which the most complex and sympathetic character is a police chief in a brutal police state, in an incestuous relationship with his twin sister, whose death is a turning point in the story (one of countless references in Dick to a dead female twin: his own twin sister died in infancy).

I came to Philip Dick’s work relatively late, but it has a big influence on me. I would find it difficult to say which is my favourite one of his books and stories, though at times I decide The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, which many people seem to pick, and which I may write about some other time. At other times I decide on Flow My Tears the Policeman Said, a wonderful book in which the most complex and sympathetic character is a police chief in a brutal police state, in an incestuous relationship with his twin sister, whose death is a turning point in the story (one of countless references in Dick to a dead female twin: his own twin sister died in infancy).

I also particularly admire his short story ‘I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon’ (I once wrote a 20,000 word dissertation on this one story, and I may at some point write more about it here.)

Although I started reading science fiction as a teenager in the seventies, I didn’t come upon Dick until some time later, and I found his work a revelation: I could use science fiction not just for sociological and political speculation, not just for ‘sense of wonder’, but to write about everything!

The first Dick book I read was Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and I was blown away by the reckless, even careless, daring with which Dick flung together ideas, bothering not at all with technological plausibility, and combining deep darkness with playful absurdity. Dick can be very funny. The opening pages of Androids are some of the funniest writing I have read anywhere, and who but Philip Dick would have a character (as in Ubik) engaging in an argument with his own sentient front door (he threatens to kick the door down, at which point the door threatens to sue him.)

Some people say Dick has good ideas but does not write well. I find this hard to understand. His writing can sometimes be sloppy – many of these books were churned out at great speed – but I envy the precision and clarity of his best prose, and at times it is really beautiful. The following is from Androids. Isidore stands in his decaying apartment in a nearly empty building, in a decaying and depopulated world:

Silence. It flashed from the woodwork and the walls; it smote him with an awful, total power, as if generated by a vast mill. It rose from the floor, up out of the tattered gray wall-to-wall carpeting. It unleashed itself from the broken and semi-broken appliances in the kitchen, the dead machines which hadn’t worked in all the time Isidore had lived there. From the useless pole lamp in the living room it oozed out, meshing with the empty and wordless descent of itself from the fly-specked ceiling. It managed in fact to emerge from every object within his range of vision, as if it – the silence – meant to supplant all things tangible. Hence it assailed not only his ears but his eyes; as he stood by the inert TV set he experienced the silence as visible and, in its own way, alive. Alive! He had often felt its austere approach before; when it came it burst in without subtlety, evidently unable to wait. The silence of the world could not rein back its greed. Not any longer. Not when it had virtually won.

But above all what stands out about Dick’s work is that, however bizarre and ludicrous the worlds he creates, the characters within them are entirely human. The author has inhabited them and looked out of their eyes (not always the case in science fiction writing, where characters are often very much seen from the outside, their characteristics added-on, rather than integral to their nature). Dick’s characters’ dramas are real, however strange (or even silly) the worlds in which they take place, just as the drama in a well-acted play is real, even if the actors’ costumes are absurd and the stage set is only bits of painted plywood.

And of course, famously, the great theme of Philip Dick, is that the so-called real world is like that too: painted plywood concealing something else. We don’t know where we are, or even who we are, but yet somehow we still really do exist.