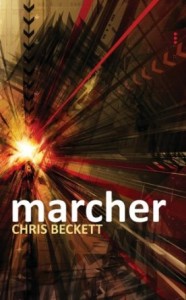

I’m delighted to say that Ian Whates’ Newcon Press, who have already published The Peacock Cloak, will also be a publishing a new, extensively revised and in places completely rewritten version of my second novel Marcher. I’m still working on the text, and the book won’t be out until mid-2014, but as you can see, Ben Baldwin has already designed this really beautiful new cover for it.

Marcher has been a sort of Cinderella among my three novels to date. I don’t mean that the others are ugly stepsisters. What I mean is that Marcher still sits in the kitchen while the others go to the ball.

Dark Eden and The Holy Machine have benefitted from editorial advice, copy-editting, and proofreading, and have come out as handsome, professionally-produced books. Marcher was a publishing project that didn’t quite come off. The US small press publisher Cosmos hoped to get a deal with big chain bookstores, but that didn’t happen. It ended up coming out as a cheap low budget paperback, sold in places like petrol stations and drugstores, with every expense spared. There was no editorial input, no proofreading. Even the kindest reviewers find it hard to avoid mentioning the typos and errors on every page. Not that I can excuse myself from responsibility. Essentially what is now available is my final draft, and it doesn’t say a lot for my own editing, let alone anyone else’s. I suppose it was a project that petered out a bit, in my own head, as well as elsewhere. But I still think that, in its own way, Marcher has as much to offer as either of my other novels, and I feel about it a bit as you might feel about a beloved child who always manages to show you up in social situations.

I grew this novel in rather a different way from my other books. The original idea came when I put together the ideas behind three different short stories. In ‘The Welfare Man’ (one of my most popular short stories), and its sequel ‘The Welfare Man Retires’ (whose full text is available here), I had built an alternative Britain with a new kind of welfare settlement in which the price for state support was formal exclusion from the mainstream of society: a kind of modern, sanitised version of the the Poor Law, the Poor Law with added Blairite spin. If you lived on state benefits you were required to live in certain fenced-off estates, and to accept a special modified category of citizenship with less rights than the rest of the population. You could not vote, for instance, and if you committed a minor offence, you might be banned from leaving the estate for a specified period of time.

Both stories dealt with an ageing social worker called Cyril Burkitt (geddit? CB), who had gone into the work to try and help people overcome disadvantage, but had ended up overseeing a bureaucratic system for monitoring and managing these special category citizens. I was a social work manager myself when I wrote it, and it reflected a worry that many social workers sometimes feel about what their job is really about.

The other story, ‘Jazamine in the Green Wood’, was a story about gender, very much in James Tiptree country, though I didn’t know it at the time, as I had somehow missed out on Tiptree’s work. However it included the idea of ‘shifters’, people who took a drug to travel between one parallel timeline and another. This was not an original idea of mine of course: it had antecedents in Philip Dick, Greg Egan (I remember a brilliant Interzone story of his called ‘The Infinite Assassin’), John Wyndham, and doubtless many others. But I saw a lot of potential in it. A shifter was a dangerous person in that he or she could escape from the consequences of his or her actions. If such people existed, there would have to be agencies to track them down and control them.

The short story ‘Marcher’ combined the idea of shifters with the world of ‘The Welfare Man’. My thinking was that, if there was a drug – I called it ‘slip’ – that could take you out of this world and into another one, than it would be the excluded and marginalised who would be most drawn to it. The story introduced a driven young immigration officer whose job was to track down shifters (essentially immigrants from another world) and a social worker called Jazamine. It was one of my most popular stories. It came first in Interzone’s annual reader’s poll, and was picked by Gardner Dozois for his Year’s Best anthology.

I wrote a sequel called ‘Watching the Sea’ which I have never liked, but which was also pretty popular with Interzone readers. The reason I didn’t like it was that there was too much tell and not enough show. It needed more space. It needed, in fact, to be a whole novel.

I was very busy at the time – being a social work team manager is demanding and stressful – and I thought I’d build up the idea by writing some other short stories set in the same world. One of them was ‘Tammy Pendant’, a first person story about a tough, brutalised young teenaged girl who was also to appear in ‘We Could be Sisters’ and ‘Poppyfields’. (This story caused a bit of controversy when it came out in Asimov’s. A woman in Winsconsin created a furore about Asimov’s being available in school libraries in the state She’d imagined that an SF magazine would be full of nice clean-cut guys having adventures in space, I suppose, and here was a story about drugs, criminality and underaged sex.)

The other was ‘To Become a Warrior’, one of my personal favourites, told in the first person by a not-very-bright and more-or-less illiterate former client of Cyril Burkitt, who was recruited by a gang of shifters, but was just too decent at heart to pass their savage initiation test.

‘Now I’ll just have to stitch all these stories together and I’ll have a novel’, I naively thought, but in the end, though the novel includes bits of all the stories I’ve mentioned, it was much harder to write this novel than either Dark Eden or The Holy Machine. The end result was seriously flawed (and not only in the purely presentational ways that I mentioned above), but also feels to me to be as rich in ideas as anything I’ve done: a book about the welfare system, and about boundaries and trangressions, and a portrait of a man who loves mirrors, and lives to guard a border which he secretly longs to cross.

I’m absolutely delighted to be able to have a second crack at this book.

Chris, apart from Dark Eden, which is brilliant, Marcher is my favourite of your writings and should be required reading on social work courses. I’m sure you will ‘improve’ it, but I wanted you to know I love it as it is.

P.s. love the new cover though.

Thanks Viv! I hope I will improve it. The ‘social work’ bits will stay pretty much as they are. Great cover isn’t it?

I’ve just read the Cosmos version of Marcher and was very impressed. The characters feel very real, presumably due in part to the authenticity of the social work setting. Congratulations.

Thanks Malcolm. Several people have told me that Marcher (the Cosmos edition) is their favourite of my books.