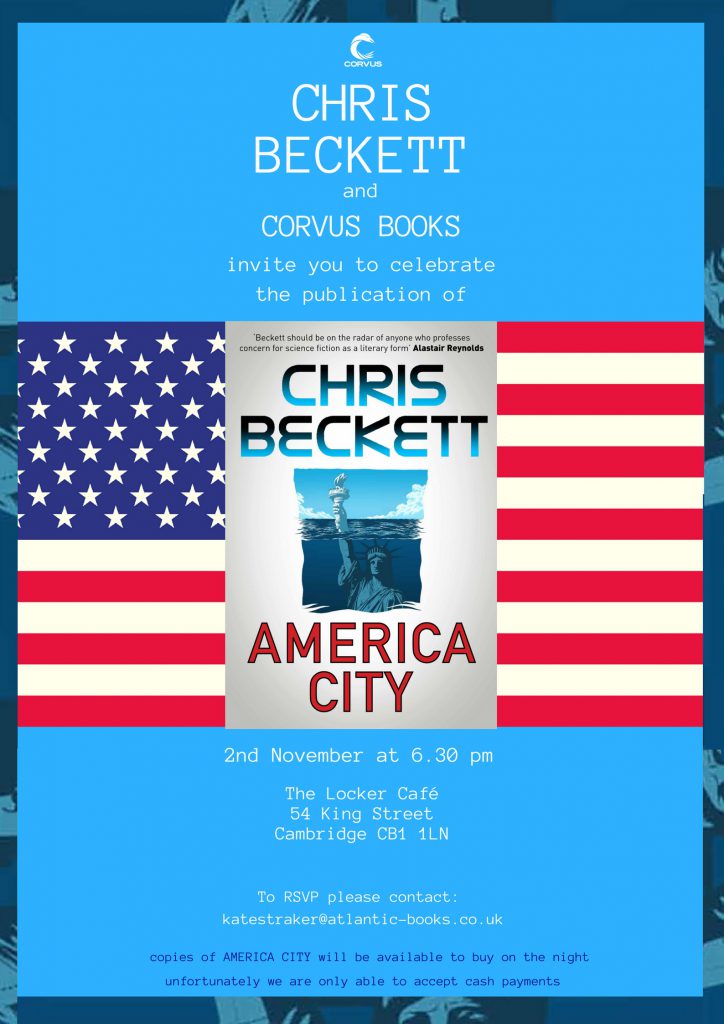

If in or near Cambridge on Nov 2nd, do come to the launch of America City at the delightful The Locker Cafe on King St. (Please RSVP to Kate Straker as per invite below, so she has an idea of numbers)

Category: News & events

Long and cut, or short and add?

I’ll be at Worldcon 75 in Helsinki next week, and I’ve been asked to take part in a panel on ‘Write Long and Cut, or Write Short and Add? (Is it better to write as much as possible and then edit out, or vice versa?)’. If you’re at the con, I hope I’ll see you there! In the meantime, here are a few thoughts:

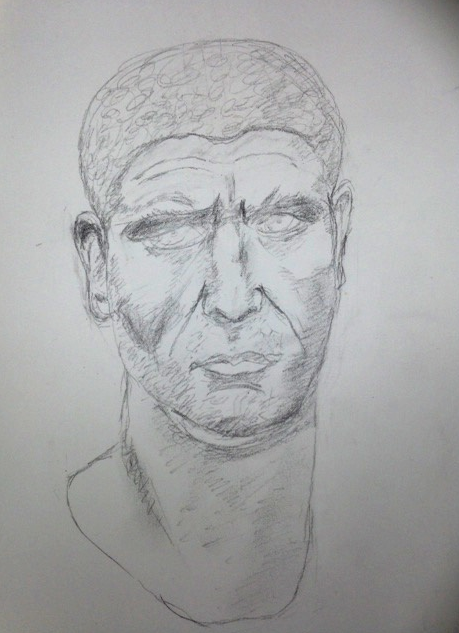

I’ve been doing a bit of drawing lately (one of my recent efforts is below) and one of the things I’ve learnt about that is that you need to be careful to get the basics right before you commit too much to the detail. If you are drawing a face for example, no amount of detail will make the picture look like its subject if the overall shape is wrong. The temptation is to get too engrossed in, say, the shadows around the eyes, only to realise later on that the eyes are too close together, and that at least one of them will need to be rubbed out completely and drawn all over again.

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

(Roman Emperor, Philip the Arab, drawn at Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge)

When writing fiction, there is a similar danger of over-committing to detail at too early a stage. This can result in beautifully crafted scenes which turn out not to fit in, but which you are reluctant to cut because you like them and have committed a lot of time to them: a lot more time can be wasted trying to make the book fit the scene rather than vice versa.

A big difference between drawing from life and writing fiction, though, is that there is no external object to act as a guide: you are not trying to reproduce something in front of you, but rather you are tapping into your knowledge, experience, and subconscious to create a new object that didn’t previously exist. Quite often, the overall shape may actually emerge out of details.

My novel Daughter of Eden, for instance, only came alive for me when I decided to tell the whole thing from the point of view of Angie Redlantern, and for that to happen, I first needed to bring Angie alive for myself by working over scenes told in her voice. Similarly, early drafts of The Holy Machine felt to me they were missing a certain something until I worked out how to write the opening pages. In both cases it was the detail of the voice, and how that voice described its world, that were the key to the entire book. I could have drafted out all the plot outlines I liked, but without knowing how the story was to be told, they wouldn’t have come to anything.

So it is a matter of writing something that vaguely resembles the story that I want to write, or the beginning of that story, and then working and reworking the material until it starts to feel lively. I always start a writing day by revising what I wrote on the previous day, and not infrequently I will go right back to the beginning and revise everything I’ve written so far before carrying on. It’s slow, but it seems to be necessary in order to dig myself down into the story.

As to whether to ‘write long and cut, or write short and add’ I don’t have a straightforward answer. What I’ve noticed is that, as a piece of writing develops, my sense of the centre of gravity of the piece gradually changes and I start to notice what I think of as expansion points and contraction points. In early drafts of the first half of Daughter of Eden, the story was told from multiple viewpoints like the other Eden books and Angie was simply one of several main characters. As I worked and reworked it, I decided Angie was to be at the centre of it, and that all the foregrounded characters were going to be women (Angie, Mary, Trueheart, Starlight and Gaia), while the stereotypically ‘male’ story of war and fighting would be pushed some way back into the mix.

So expansion points are places in the text which seemed of relatively minor importance to start with but are now more important, perhaps to the point where they now feel like the story. In some cases, material which was little more than a connector between two scenes, can turn out to be more important than the scenes themselves. One set of expansion points in Daughter of Eden concerned the Davidfolk’s rituals around circles and the idea of homecoming. That stuff was just a detail at first, one of those things you put in to make a scene a bit more concrete, but it became absolutely crucial to the overall shape of the book, and so I expanded and developed all that, not only by including more detail (the circles, the song, the dots on the foreheads of guards…), but by incorporating those ideas and beliefs into Angie’s thinking.

Contraction points, on the other hand, are places in the text whose importance, or necessity, has diminished over time, so that they need cutting back, or cutting out entirely. In the case of Daughter of Eden this included scenes seen from the viewpoint of male characters, some of which I cut altogether, while others were shortened and retold as observed by Angie, or reconstructed by Angie thirdhand from stories told by others, or relayed by Angie from scenes that Starlight participated in and told her about.

So I suppose my conclusion from all this is, write what you can, and be prepared both to expand and cut.

Angie Redlantern speaks

Daughter of Eden is now out as an audiobook from Audible. It’s read by Imogen Church and, listening to the sample, I think she’s done a really wonderful job of it. I felt I was listening to Angie Redlantern herself telling the story. Which was a strange and rather moving experience, given that Angie (possibly my favourite Eden character) came out of my own head. Click on this link for the free sample and judge for yourself.

My Next Novel

My next novel, America City, is now at the proof-reading stage. It even has an Amazon page already. I’m getting rather excited about it. It’s starting to feel real.

This book will be a new departure for me in that all three of its predecessors were set on my sunless planet, Eden, but this takes place in North America in the twenty-second century. No more glowing forests or hmmmphing trees, though I think readers may still be able to spot links of various kinds between America City and the Eden books.

Like my previous novels it’s to be published in the UK by Corvus, and should be available from 2nd November.

And there’s another book behind it too, my next short-story collection, Spring Tide, already good to go, and also to be published by Corvus. (It also has an Amazon page). It should be coming out in the UK in the Spring of 2018. This is a new departure too. I have published two previous collections, and one of them won me a prize, but this is my first collection to consist entirely of previously unpublished stories, and my first ever published fiction, whether in the long or short form, that really could not be defined as science fiction.

во тьме здема

Headland anthology

I’m very pleased that my short story ‘Monsters’, first published in Interzone way back in 2003, will be appearing, in very distinguished company, in the Headland anthology, published by Edge Hill University Press to mark 10 years of the Edge Hill Prize. The Edge Hill Prize is the UK’s main prize for single author collections of stories (of any genre) and winning it for my collection, The Turing Test, was a huge breakthrough in my writing career.

Although it’s not the story that people most often mention when they read The Turing Test, ‘Monsters’ is a personal favourite of mine, perhaps because, although autobiographical elements are present in almost all my fiction, they are particularly to the fore here in this story about how writers both use and are held back by their demons, and about a poet’s emotionally stifling relationship with his mother.

Here’s the blurb about me and the story on the Edge Hill website.

Marcher on offer

Mother of Eden interview

Here is an interview with Paul Semel about Mother of Eden. (Many thanks, Paul, for your interest.) Paul also interviewed me last year about Dark Eden, and that interview is here.

Incidentally Mother of Eden is out in the UK on June 4th (in spite of some slightly confusing statements on Amazon UK, which the publishers are currently fixing). It’s out in the US this week.

In the picture I’m standing on a Roman road outside Cambridge, where I go to walk our dogs. Sort of appropriate really, in a book which talks a lot about living among the residue of the past.

Mother of Eden en Francais

I’m delighted to say that Presses de la Cité (who already publish the French version of DARK EDEN) have acquired French rights in MOTHER OF EDEN.

Dortmund

This is me at Dortcon, with the other guests of honour, artist Lothar Bauer on the left of the picture (a man of few words, who says his pictures speak for him: we are flanked by two of them here) and fellow SF writer Karsten Kruschel on the right.

As with Sferakon last year in Zagreb, I was a little daunted in prospect by the idea of attending a convention whose primary language would not be English, but (also as with Sferakon) I was made extremely welcome, people put themselves to a lot of trouble to make sure I was included, and I had a great weekend. Special thanks to Arno and Gabi (my main hosts), Michael who first suggested inviting me, and Gregor who acted as my interpreter when one was needed (making me feel like some kind of international statesman, as he murmured into my ear.)

I know a huge amount of work and worry, over a long period of time, goes into planning these events, which most attendees (including me) don’t really see. What I see, and most attendees see, is a little peaceful island, where gentle and imaginative people can gather for a couple of days of conversation and friendship and playfulness.

This was my first real visit to Germany. Fascinating listening to German spoken all around me. Perhaps because, from an early age, my sisters and I were cared for by German au pairs, I’ve always liked the sound of the language. I find it musical, where many English people find it harsh, and could quite happily just sit and listen to its cadences, even if I didn’t have someone to interpret. The tantalising thing about it is that, though I can’t understand it, it’s so obviously a close cousin of English that I can’t quite let go of the idea that, if only I tried hard enough, I could.

It’s interesting how every country has its stories, its past events, it’s preoccupations, which it must keep going over and over, just as individuals have events in their own lives that they must visit and revisit over and over: the old DDR and what had happened to it when Germany was unified, for instance, was clearly one such topic, even more than twenty years on.

My fellow writer and guest of honour Karsten grew up in the DDR. He told me all SF in the DDR had to depict a socialist future (so as not to violate the Marxist creed of the inevitable triumph of socialism). When he studied for a PhD thesis on dystopian literature, he had to have special permission to look at George Orwell’s 1984, which was held in the university library but was forbidden to the general public. He had to go to a special room to read it.

Now to me, that sounds like a scene from an SF novel in itself.